2016 "cold" SMS voter registration test results

Can you use unsolicited text messages to register voters? In 2016, this was a novel question.

Project conception, fundraising, staffing, and implementation by Debra Cleaver (VoteAmerica). Experiment design and evaluation by the Analyst Institute and Christopher Mann (Skidmore). Technology platform built by Hustle.com. Almost all funding for this project came from the Y Combinator Investor Community after Debra Cleaver pitched this idea during YC's Summer 2016 Demo Day. The below was extrapolated from a study originally published in 2017.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In 2016, a national civic organization (NCO) partnered with the Analyst Institute to run a series of experiments in 2016 to evaluate the influence of text messages on civic engagement. This particular test examined the impact of “cold” SMS messages on voter registration and turnout. This test was the first-ever large-scale well-powered study to measure the influence of voter registration text messages on net registration and turnout and the cost-effectiveness of SMS voter registration programs. This was also the first-ever use of "cold" SMS to register voters. This test was designed to answer the following research questions:

- What is the impact of SMS voter registration messages on net registrations? What is the cost per net registration?

- What is the impact on turnout of SMS voter registration messages? What is the cost per net vote?

Key findings

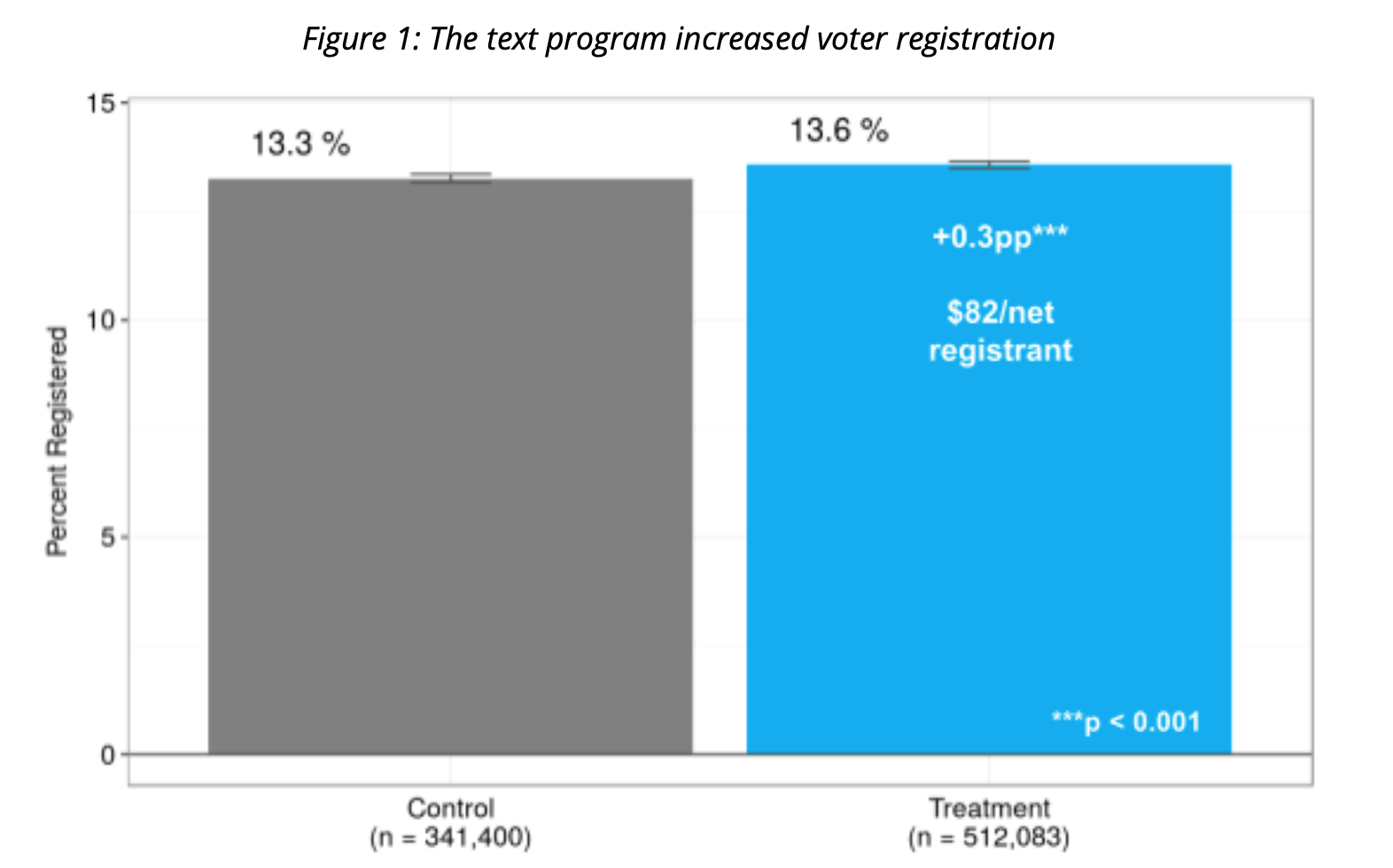

- The SMS program increased voter registration by a statistically significant 0.3 pp (p < 0.001), generating 1,601 registrants at a cost of $82 per net registrant (or 12 registrants per $1,000 spent).

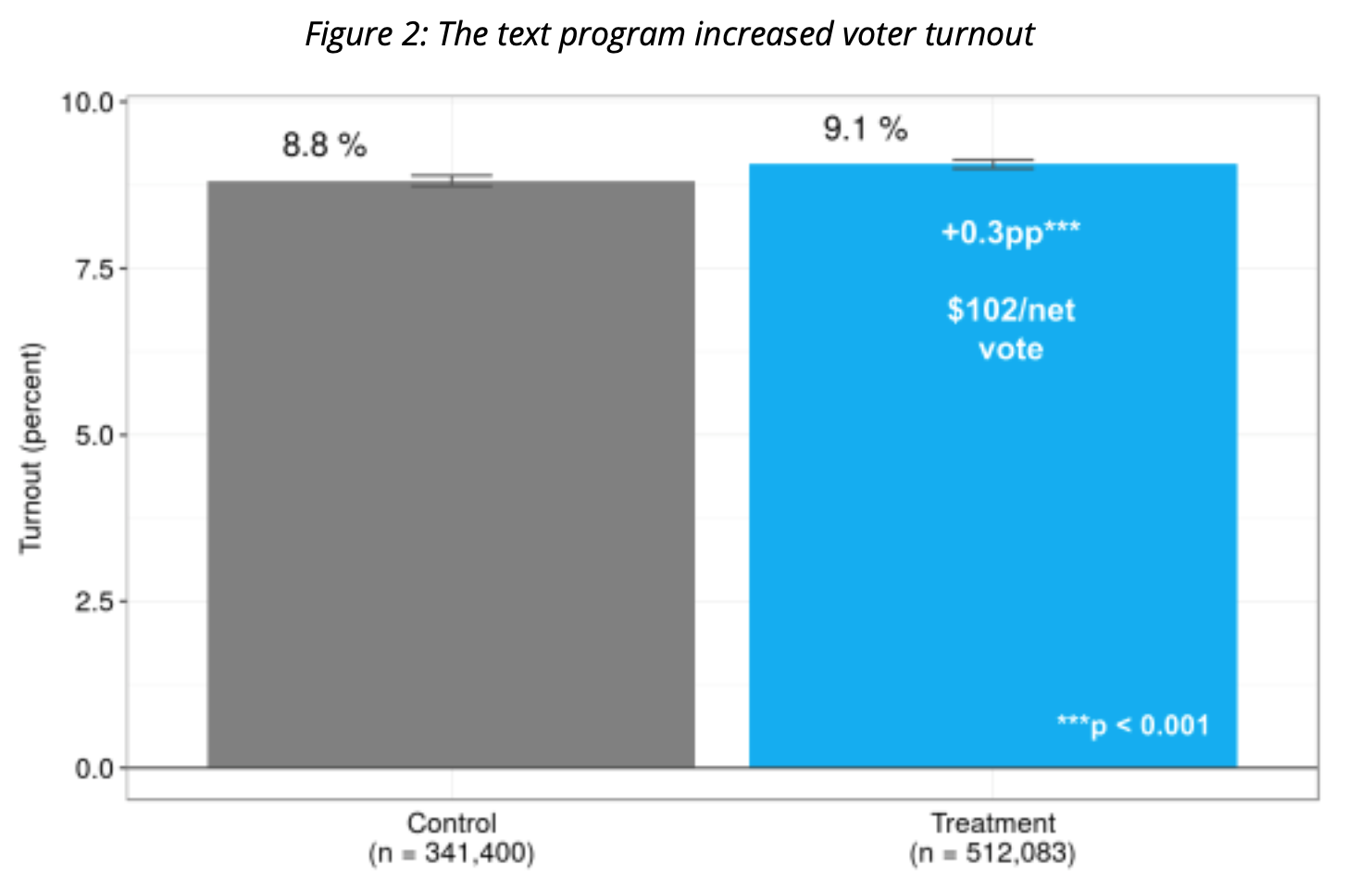

- The text program also boosted voter turnout by a statistically significant 0.3 pp (p < 0.01), yielding votes at cost of $102 per net votes (or 10 votes per $1,000 spent).

- The number of net registrants was much smaller than the number of forms submitted on NCO's website as part of the program. In the text program, targets were sent links to an online form that Vote.org uses to collect information from targets. The purpose of this form is to help Vote.org build a list of individuals to contact in future voter engagement and mobilization efforts. Only after completing the form were targets sent to official Secretary of State voter registration websites. While the program generated about 1,601 net registrants, 23,621 forms were submitted on NCO’s website. The cost per NCO form submitted was $6 (or 180 forms per $1,000 spent). Given the multi-step process of registering online via this SMS program, the cost per NCO form submitted is not equivalent to the cost per registration form submitted. The cost per registration form submitted is not fully observable given current limitations in state registration technology.

- The disparity between net registrants and forms submitted is likely due to the submission of forms by non-targets (potentially due to poor cell phone number quality), attrition between form submission and official registration, and registration of some targets before the start of the text program. We estimate that only about one-third of forms submitted were from intended targets; that between 19% and 59% of individuals who submitted Vote.org forms actually ended up registering after the start of the text program; and that roughly 7% of the initial target universe may have been registered prior to the beginning of the text program.

Key takeaways

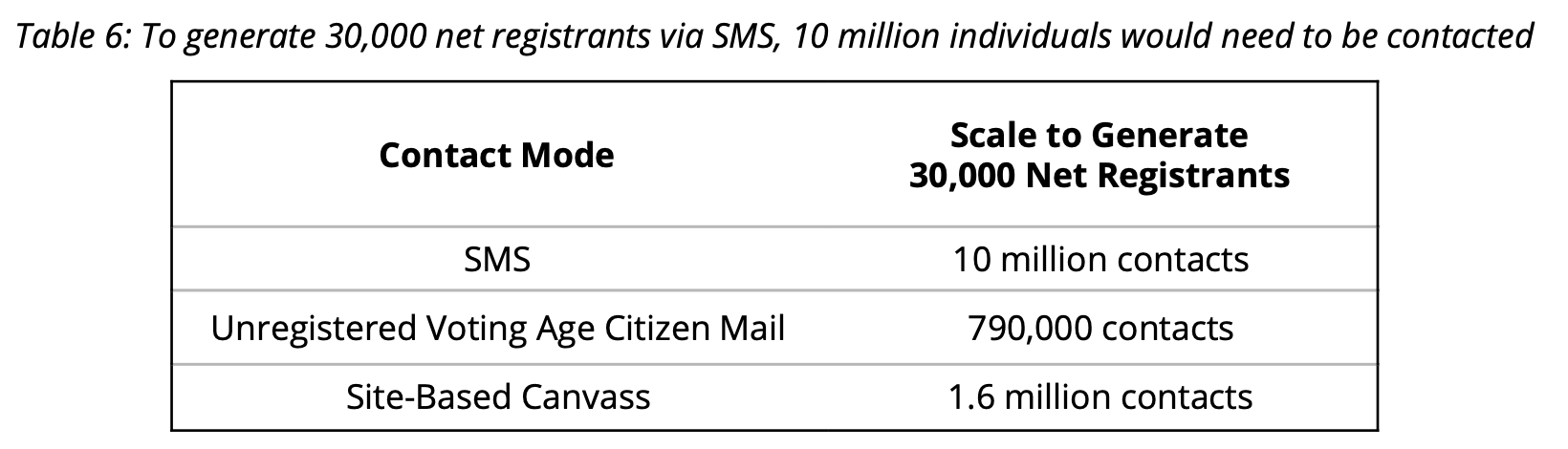

- Voter registration text messages can be a cost-effective registration tool, but it may be difficult to generate a large number of net registrants using texts. The cost per net registrant was competitive with that observed in other 2016 presidential election year site-based voter registration programs. However, the effect of text messages on registration was smaller than that observed via traditional modes of contact. This means that fewer net registrants were generated per contact, and thus, larger program universes are needed to yield a comparable numbers of net registrants. In particular, to produce 30,000 net registrants via text, a universe of 10 million individuals would need to be contacted, which in many cases is impractical.

- Voter registration text programs are an effective and cost-efficient voter mobilization tactic, generating turnout effects at a magnitude and cost on par with other presidential election year GOTV programs.

- More research and work is needed to ensure accurate measurement of text program effects and optimize the efficacy of text programs. To better understand why forms were submitted by non-targets, additional research is needed to further validate the quality of unregistered voter cell phone lists. Moreover, to reduce attrition between form submission and official registration, Vote.org should continue its work to optimize its platform and make the transition from form submission to official registration more seamless.

BACKGROUND

Numerous studies have examined the efficacy of various voter registration tactics, including mail, site-based canavasses and door-to-door canvasses. Results from these tests indicate that mail is generally the most cost-effective tactic for registering voters, with a cost per net registrant of about $15 to $20. Second to mail, site-based voter registration programs are also relatively cost-effective, with a cost per net registrant of about $25 to $40 in non-presidential election years and roughly $100 in presidential election years. Door-to-door canvassing has been found to be the most expensive, with a cost per net registrant of about $130 in off-year elections and a prohibitively high cost of about $715 per net registrant in midterm elections.

Voter registration programs via traditional modes of contact have also been shown to be effective and cost-effective GOTV strategies. Research conducted in 2012 showed that voter registration programs via mail increased turnout by roughly 1 to 1.6 pp and had a $22 to $36 cost per net vote. In contrast, a 2012 study found that GOTV mail programs only boosted turnout by about 0.5 pp to 0.9 pp and had a cost per net vote of $37 to $73.

With the rise of new modes of voter contact, progressive organizations and campaigns are increasingly interested in understanding how new technologies stack up against traditional methods when it comes to engaging voters. One of the most promising new methods for communicating with voters is SMS. Indeed, previous tests in 2006, 2014, and 2016 have shown that text messages to people who have opted-in to receive texts can be effective at mobilizing voter turnout, with SMS GOTV effects between 1 pp to 3 pp. Yet, to our knowledge, there is no prior large-scale experimental study on the effect of SMS on voter registration.

This test was the first-ever large-scale well-powered study to measure the influence of voter registration text messages on net registration and turnout and the cost-effectiveness of SMS voter registration programs. This was also the first-ever use of "cold" SMS to register voters.

EXPERIMENT DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION

Experimental universe

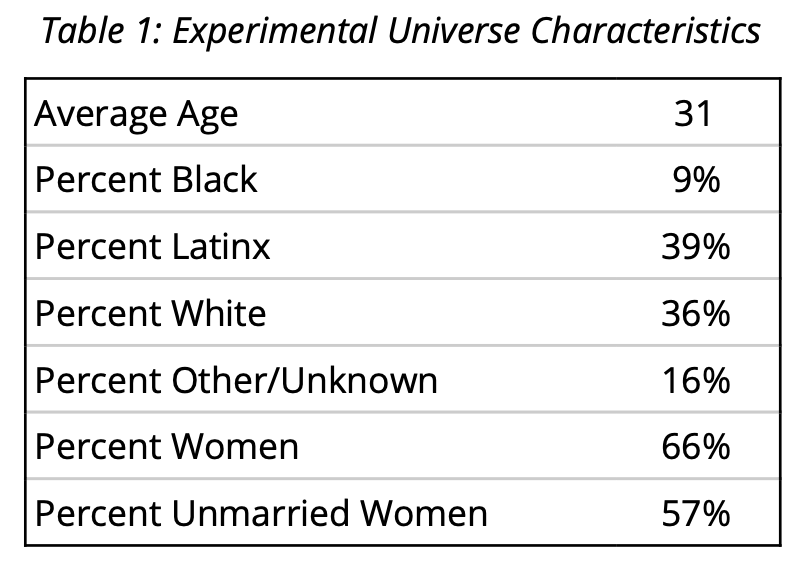

The universe for this test included 853,483 cell phone numbers of unregistered voters. The list was acquired from TargetSmart and was comprised of people of color under 40 as well as unmarried women under 35 in states with online voter registration. States included in the test were AL, AZ, CA, CO, CT, GA, IA, IL, IN, KS, KY, LA, MA, MD, MN, MO, NV, OR, PA, SC, UT, VA, and WA. The universe was limited to states with online registration in order to ease the workflow between receiving the voter registration text messages and filling out registration forms.

Table 1: Experimental Universe Characteristics

Experimental conditions

Targets were randomly assigned to one of two conditions:

- Voter Registration SMS: People in this group were sent voter registration text messages (n = 512,083 targets)

- Control: People in this group were not sent voter registration test messages (n = 341,400 targets)

Targets were randomized at the household level, defined by the mailing address, stratifying on state, household gender composition, household race composition, mean household age, and household size. See the Technical Appendix for details on post-randomization covariate balance checks.

Experimental implementation

NCO obtained a list of cell phone numbers in their target universe from TargetSmart. Analyst Institute then randomized the list of cell phone numbers into experimental conditions and NCO used Hustle to deliver the assigned text messages to targets in the treatment condition.

Text messages were delivered between September 27th and October 25th. Delivery dates were staggered according to each state’s voter registration deadline, so that texts were delivered approximately a week before the deadline.

Analyst Institute advised NCO on the text messages scripts, using guidance from earlier pilot tests conducted in partnership with NCO and Chris Mann to inform the content of messages sent. Although the messages varied slightly by state and voter registration deadline, messages followed a similar pattern, encouraging people to register to vote via NCO’s platform. Examples messages can be found below

Links sent to targets were unique to the test, although all targets received the same link. When clicked, the links directed individuals to an online form on NCO’s website. NCO uses this form to collect information from targets and to build their list of contacts for future voter outreach. After submitting the NCO form, individuals were redirect to their Secretary of State voter registration website where they could officially register.

In addition to clicking through the link sent in texts, voters could also respond to texts received with questions or clarifications as well as opt-out messages.

Contact and response rates

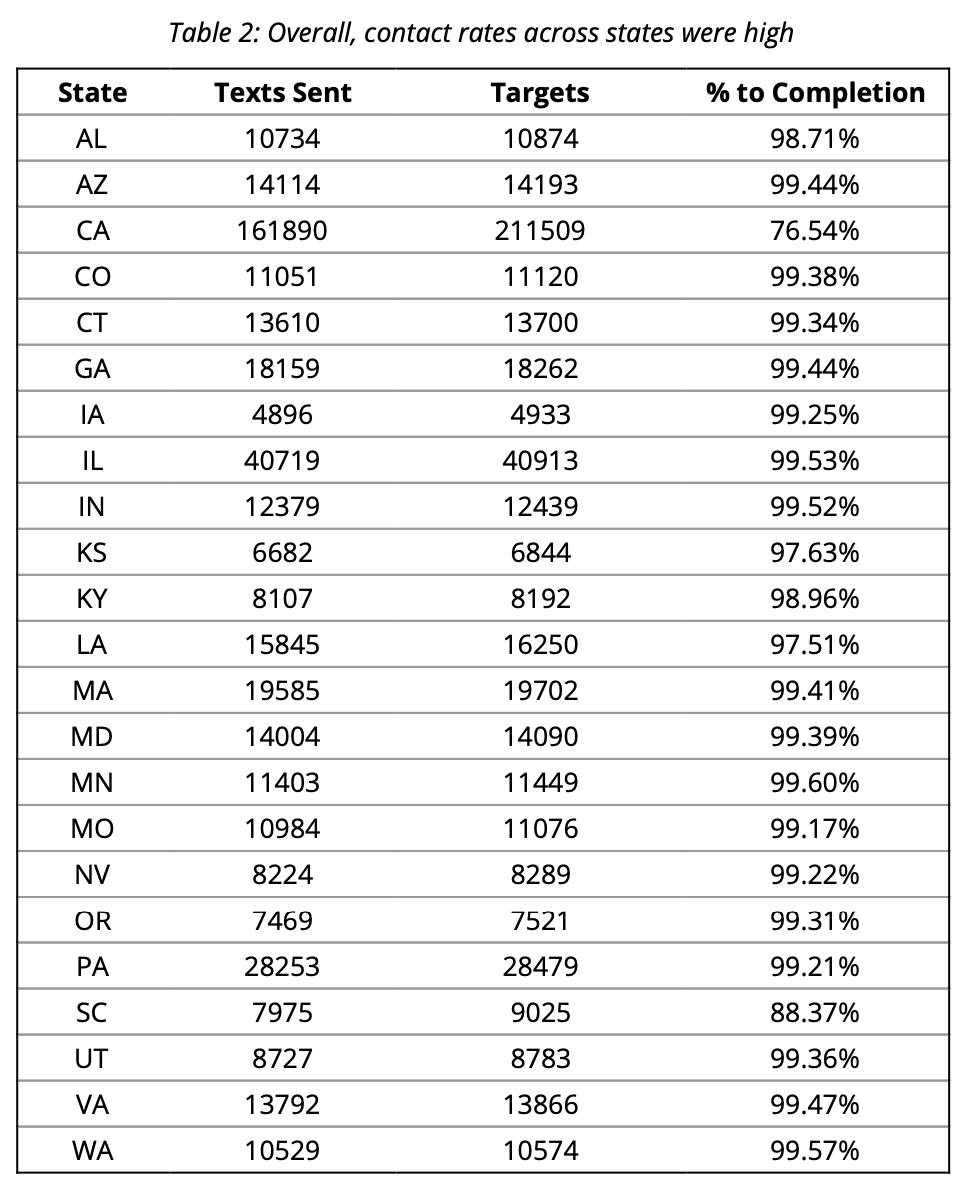

A total of 459,131 texts were sent to targets. The overall completion rate (i.e., the share of targets receiving texts) was 90%, with most targets receiving at least one text message. There was minimal variation in completion rates by state (Table 2). With the exception of CA and SC, between 97% and 100% of the treatment universe received at least one text.

The response rate to text messages was low, with approximately 5.6% of targets responding in some way. As responses to the program were not systematically captured, the content of responses is not part of this analysis. However, most responses appeared to contain questions about the content of the texts.

Table 2: Overall, contact rates across states were high

Outcome measurement

The outcomes in this test were (a) voter registration and cost per net registration and (b) turnout and cost per net vote. Registration and turnout were measured using data from the TargetSmart voter file. Costs per net registration and vote were calculated using cost data provided by NCO.

RESULTS

Main results

The text program had a positive influence on voter registration (Figure 1), increasing registration rates from 13.3% in the control condition to 13.6% in the treatment group. This 0.3 pp boost in registration rates is statistically statistically (p < 0.001). The program generated 1,601 net registrants at a cost per net registrant of $82 or 12 registrants per $1,000 spent.

Figure 1: The text program increased voter registration

The text program also increased voter turnout (Figure 2). Roughly 8.8% of individuals in the control group voted, while 9.1% of targets in the treatment group turned out. This 0.3 pp difference is statistically significant (p < 0.001). The text program generated 1,278 net votes at a cost per vote of $102 or 10 votes per $1,000 spent.

Figure 2: The text program increased voter turnout

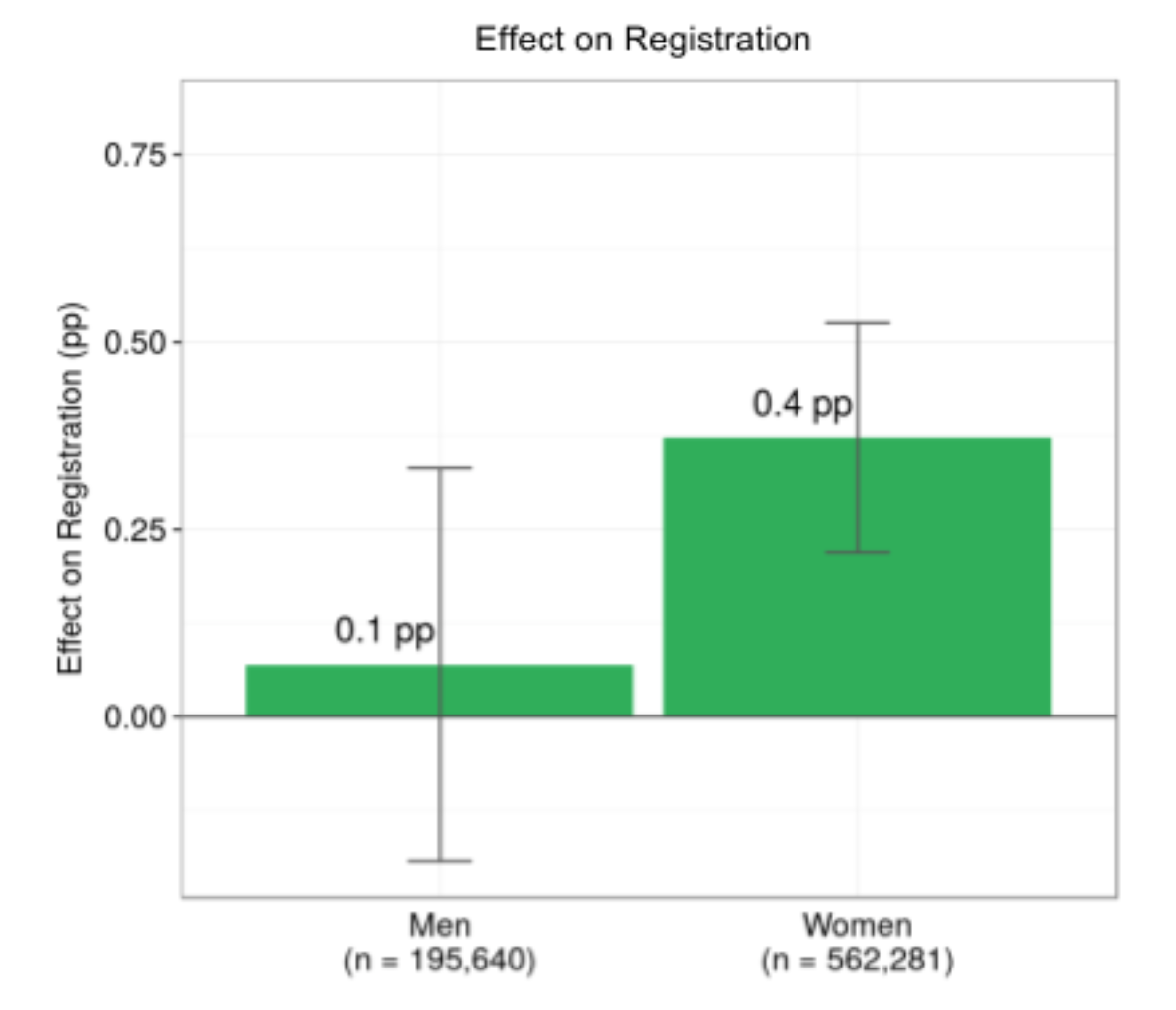

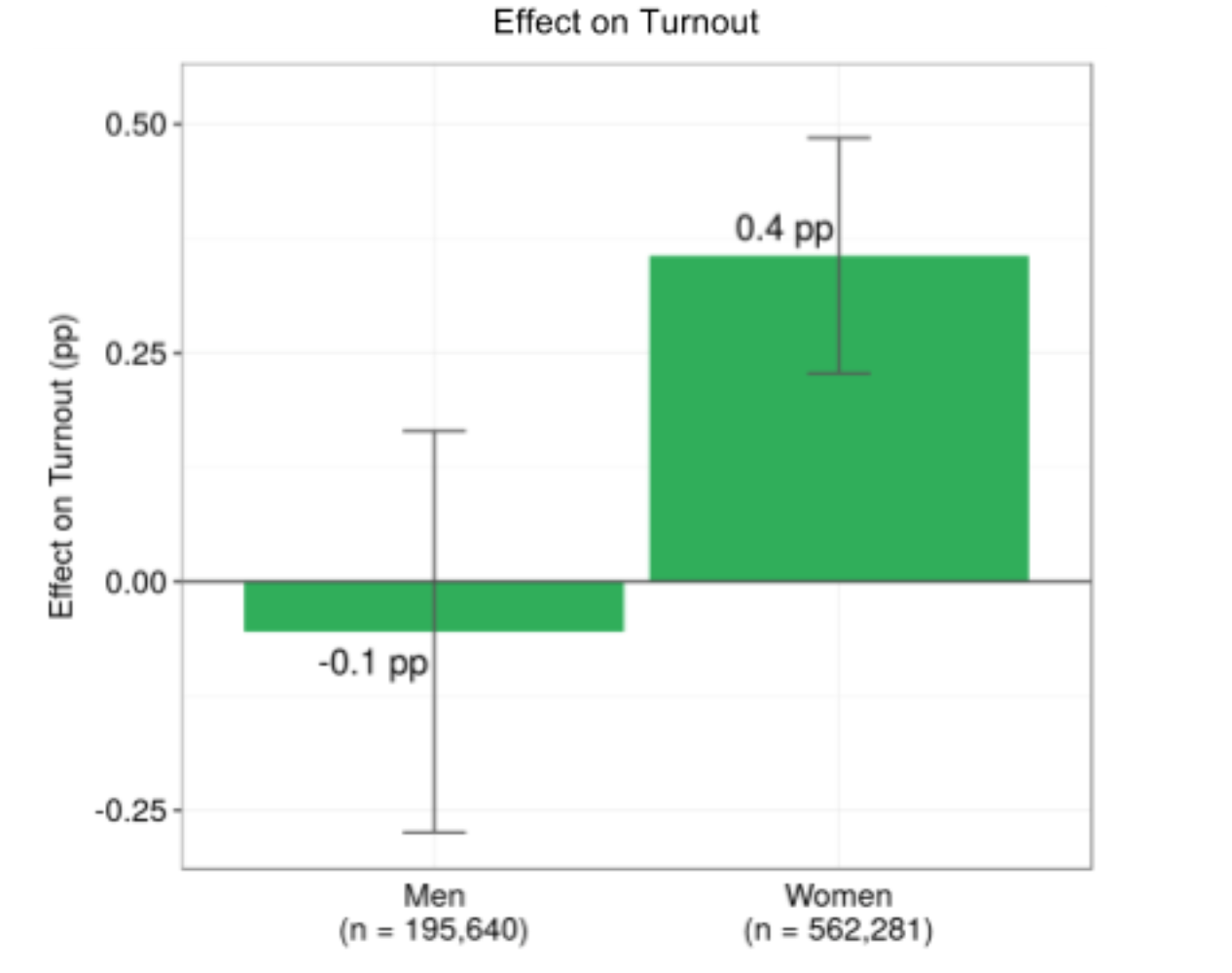

Variation in treatment effects

The effects of the text program on registration and turnout were examined by voters’ demographic traits, including age, race, gender and marital status, and by whether or not individuals lived in a battleground state. While effects did not appear to vary by age, race, marital status or registration in a battleground state, there was some evidence of heterogeneity in effects by gender, with women being more treatment responsive than men (Figure 3). The mechanism underlying this pattern is unclear, however. Further testing is needed to validate these gender differences before concluding that women are uniquely responsive to voter registration text programs.

Figure 3: Women may have been more responsive to the text program

Comparing net registrants to forms submitted on NCO website

The text program generated 1,601 net registrants. But, 23,621 forms were submitted on NCO’s online platform as part of the program. The cost per NCO form submitted was $6 (or 180 forms per $1,000 spent). This cost per NCO form submitted is not directly comparable to the cost per registration form submitted. Individuals who submitted NCO forms online still had to register via their official Secretary of State’s website after completing a NCO form; and as is discussed below, not all who submitted NCO forms online made it through to officially register. It is not possible to track the true number of registration forms submitted by people responding to the text program, as most states do not provide feedback on whether an applicant who is directed to their online registration portal from a third party successfully completes the registration process. As a result, the cost per Vote.org form submitted should not be compared to the cost per registration form submitted in mail or site-based canvass tests.

We investigated several potential explanations for the difference in net registrations and forms submitted with the data available. The results of this analysis are reported below. Overall, they indicate that the disparity is likely due to at least three main causes.

Explanation 1: Roughly two-thirds of form submitters were not the intended targets

One possible explanation for the difference between net registrants and forms submitted is that forms were submitted by people other than the intended targets. The initial target list may have incorrectly identified cell phone number users and thus, text messages may have been received by people other than the intended target. Moreover, links texted may have been shared by intended targets with other people, causing non-targets to submit forms online.

To evaluate whether forms were submitted by people outside the target universe, we compared data on initial targets to data on form submitters. The results from this comparison suggest that Vote.org form submitters were in many cases not the intended target.

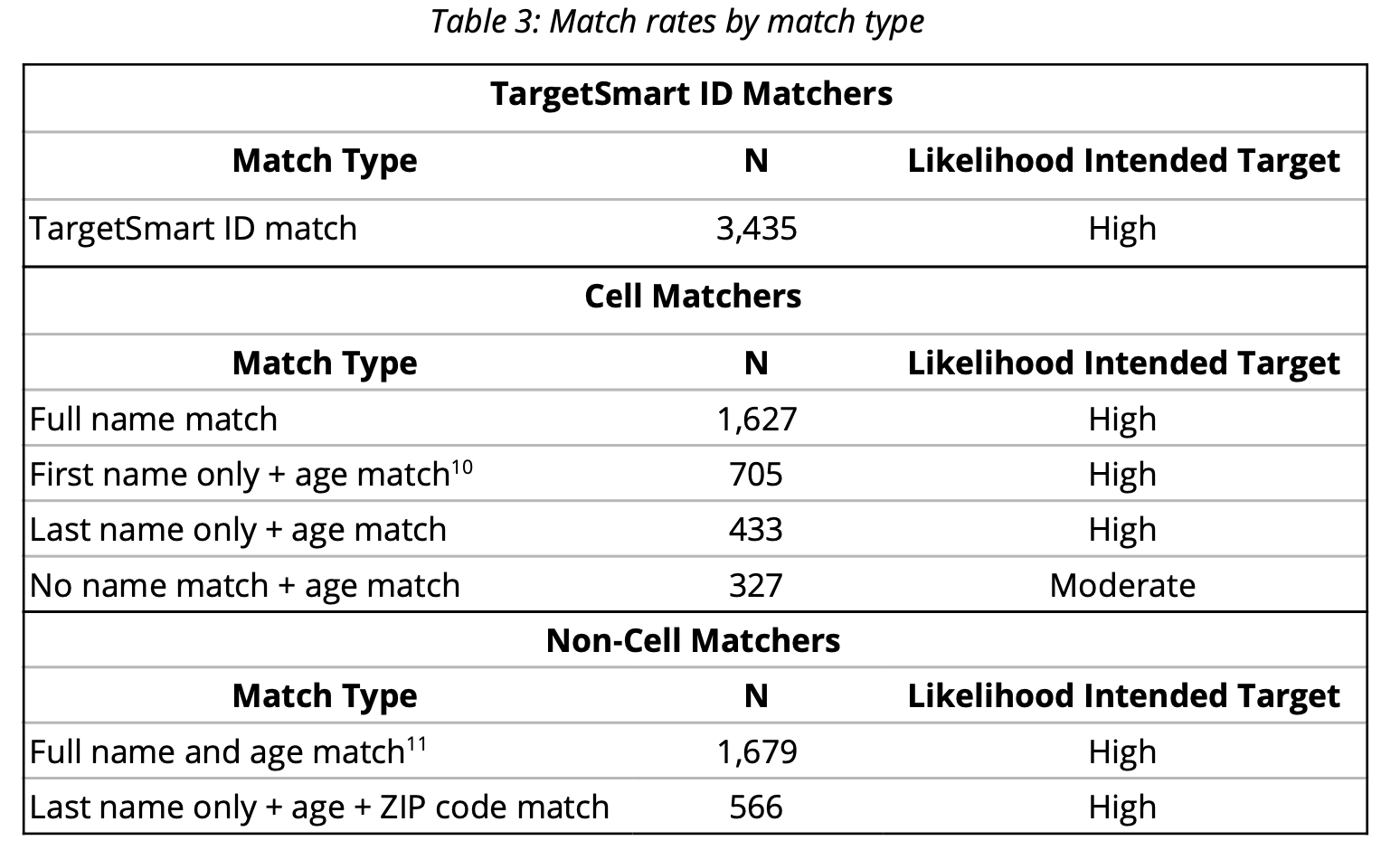

- First, we used TargetSmart IDs to match individuals in the original target universe to those who submitted forms. 3,435 people (15% of forms submitted) were matched using

- Among those who could not be matched based on TargetSmart IDs, 8,018 people (34% of forms submitted) could be matched to form submissions based on phone numbers listed in the original target data and on forms submitted. 2,765 of these cell matchers (12% of forms submitted) had suffciently comparable name and age data across data sources to indicate a high likelihood that intended targets had been reached and submitted a form (Table 3). This increases to 3,092 (13% of forms submitted) if matches indicating a moderate likelihood that intended targets had been reached are included.

- Among those who could not be matched based on TargetSmart IDs or phone numbers, 2,245 people (10% of forms submitted) had some combination of matching name, age and ZIP code data across data sources to suggest that intended targets had been reached and submitted a form (Table 3).

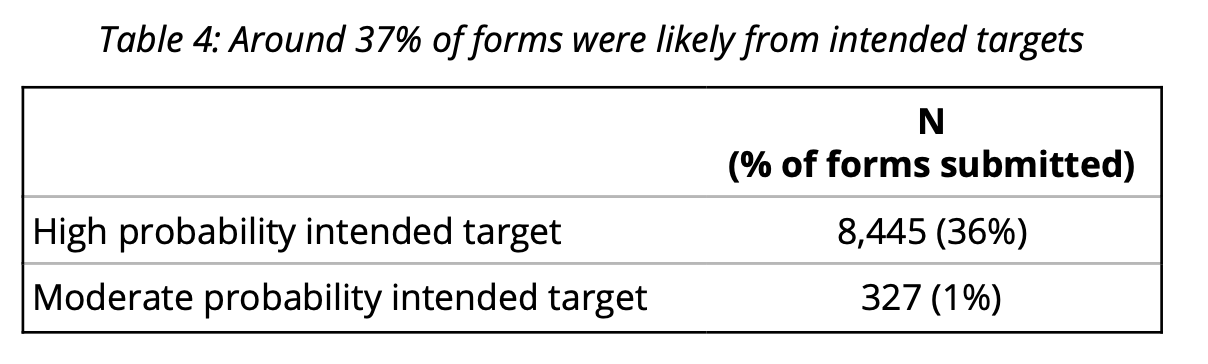

Overall, we estimate that about 37% percent of forms were submitted by intended targets in the universe (Table 4). Accordingly, it is possible that the true e�ect of the program on registration in the experimental universe was higher than estimated above, being potentially about 0.8 pp.

Table 3: Match rates by match type

Table 4: Around 37% of forms were likely from intended targets

Explanation 2: There was attrition between NCO form submission and SOS website registration.

A second possible explanation for the difference between net registration and forms submitted is that there was attrition between NCO form submission and registration on oficial Secretary of State websites. Examining registration rates, we confirmed that not all people who submitted NCO forms made it through to oficially register via SOS websites. Among form submitters, about 59% of people were registered. This percentage drops to 19% when attention is limited to just those who had registration dates after the start of the text program.12 As registration dates on the voter file can be unreliable, we estimate that between 19% and 59% of individuals who submitted NCO forms actually ended up registering to vote after the start of the program.

Explanation 3: The universe may have included people who were already registered prior to the start of the program

A third possible explanation for the disparity between net registration and forms submitted is that the universe included people who were already registered prior to the start of the program on September 27. Although the target list may have only included unregistered voters when the list was pulled, targets may have registered after the list was obtained on September 20th but before the program began. This would have reduced program effects on net registration, as the program would have been served to those who were already registered to vote.

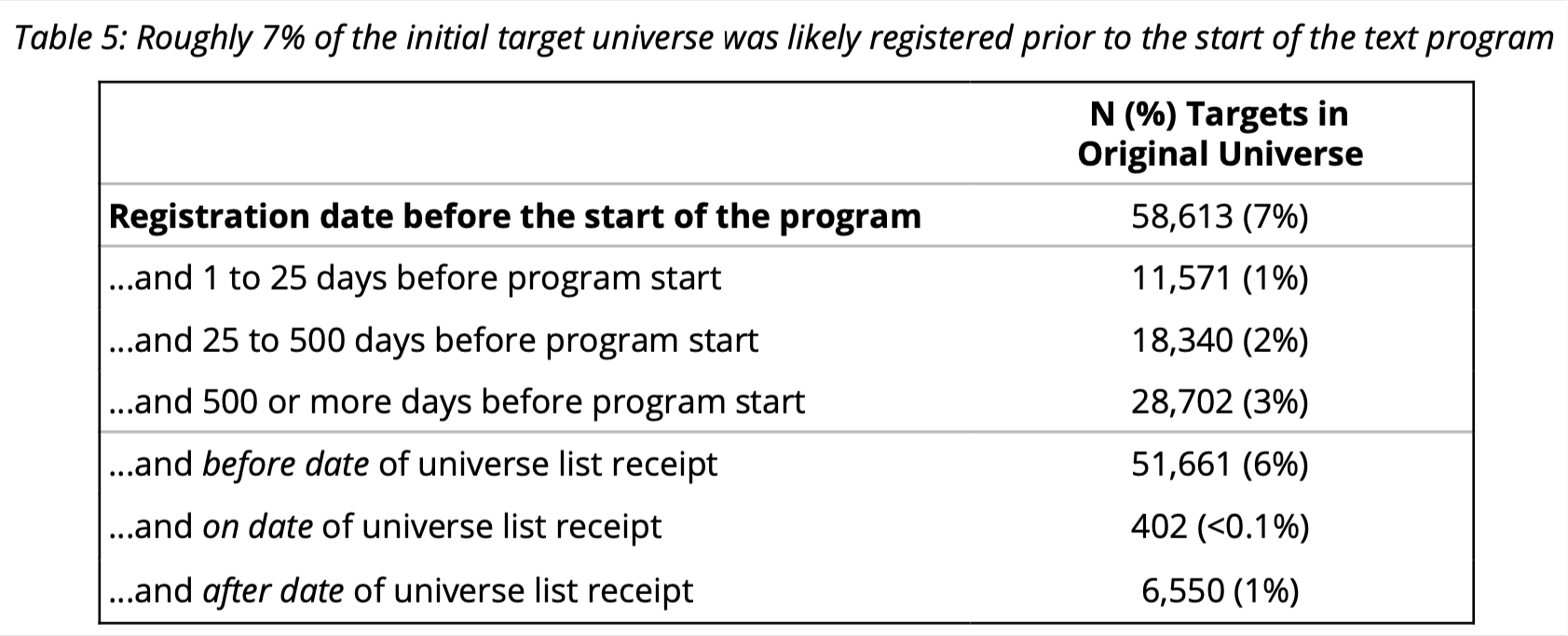

There is some evidence to support this hypothesis. Among targets identified as registered following the post-election voter file update (114,784 people), about half had registration dates before the start of the text program (Table 5). Most of these targets had registration dates indicating that they were registered well before the start of the text program and before the target list was received. This means that roughly 7% of the initial target universe may have been registered prior to the beginning of the text program, with 6% being registered before the target list was obtained.

This finding is unexpected, as the target list was only supposed to include unregistered voters. Indeed, all targets were listed as “unregistered” based on the “registration status” field in the original universe data file received. As previously mentioned, registration dates on the voter file can be unreliable. Given the limitations of the registration date data, while there is some evidence to suggest that individuals included in the universe were already registered prior to the start of the test, this evidence must be interpreted with caution.

Table 5: Roughly 7% of the initial target universe was likely registered prior to the start of the text program

DISCUSSION

The test results demonstrate that voter registration text messages can increase registration and turnout. Comparing the SMS program registration effect to that via other modes of contact, the text program did have a smaller impact on registration (0.3 pp) and a higher cost per net registrant ($82) than voter registration mail programs during presidential election years. In one study in 2012, voter registration mail increased registration rates by between 1.8 pp and 3.8 pp depending on whether mail was sent to movers, 18 year olds, or listed but unregistered voting age citizens. The 2012 mail program had an average cost per registrant of about $15. Comparable estimates from 2016 voter registration mail tests are not yet available.

Although the text program did have a lower cost per net registrant than presidential election year site-based canvass programs, the small magnitude of effect suggests that registering large numbers of voters via text may be infeasible in most cases. For example, with only 3 net registrants produced per 1,000 individuals contacted, text programs must contact 10 million individuals to generate 30,000 net registrants (Table 6). In contrast, with a 3.8pp effect on net registration, a mail program to unregistered voting age citizens would only need to contact about 790,000 individuals to generate 30,000 net registrants. With a 1.9pp effect on net registration,15 a site-based canvass would need to contact about 1.6 million individuals. In short, generating a satisfyingly large number of net registrants may be a challenge via SMS.

Table 6: To generate 30,000 net registrants via SMS, 10 million individuals would need to be contacted

The text program’s effect on voter turnout conforms other research conducted in 2012 showing that voter registration programs can be an effective and cost-effective GOTV strategy. The program’s turnout effect (0.3 pp) and cost per vote ($102) are comparable to the effects and costs observed in other presidential election year GOTV programs. Yet, voter registration by SMS does not appear to outperform voter registration by mail as a GOTV strategy. Based on 2012 test results, voter registration mail effects on turnout are likely larger and costs per vote are likely smaller than those in voter registration text programs.

More research is needed to ensure accurate measurement of text program effects. That non-targets submitted forms via Vote.org’s platform indicates that non-targets may have also registered in response to the text program. From the perspective of measuring program effects, this is problematic as outcomes were only tracked for targets. As previously discussed, one potential reason non-targets may have submitted forms is that they were inadvertently texted as part of the program due to errors in unregistered voter cell lists. Although the assessment of forms submitted above made the best attempt to use the data available to identify how many forms were collected from non-targets, it remains unclear to what extent non-target form submission is due to low quality cell phone numbers versus other factors (e.g., link sharing among family and friends).

Additional research is needed to fully evaluate how reliable unregistered voter cell phone number lists are and the extent to which their lack of reliability threatens our capacity to measure effects on unregistered voters. Importantly, such work would lend insight into the quality of unregistered voter cell lists, generally, instead of just lists of numbers among those inclined to submit forms via Vote.org’s platform. As the assessment of forms submitted above only focused on Vote.org form submitters, inferences regarding the overall quality of unregistered voter cell numbers based on that analysis are limited. They may only apply to those apt to respond to voter registration text messages. Beyond evaluations of unregistered voter cell lists, similar assessments of list quality should be conducted for lists of registered voters. This would help clarify whether concerns regarding list quality raised here apply in studies of “cold” SMS messages to registered voters as well.

More work is also needed to reduce attrition in the text message to registration pipeline. Future research should assess what strategies enhance conversion rates from SMS receipt to SOS registration. Additionally, NCO should continue its work to make the transition from NCO form submission to voter registration more seamless. Such efforts will help optimize the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of text message voter registration programs.