2018 measuring the effects of “e-sign” on voter turnout

Program conception, design, and fundraising by Debra Cleaver (VoteAmerica). Program execution by a national civic organization (NCO). Analysis by Pantheon Analytics. The below was originally published on September 27, 2019

Executive Summary

In 2018, NCO implemented an option on its absentee signup and registration pages that allowed users to sign and submit their forms electronically. In this analysis, we find that absentee tool users who chose E-Sign were much more likely to successfully vote absentee – and to vote overall – than those who chose to print their forms, despite the fact that E-Signers had lower pre-existing vote propensity scores. Users of the registration tool’s E-Sign option also had greater success in registering than those who printed their forms (though less success than those who opted to be redirected to their state’s online registration system).

These improvements could be attributed to E-Sign, or they could be due to unknown self-selection factors. Indeed, analyses of NCO’s users in the weeks just before and just aer the E-Sign implementation do not show higher overall success rates aer E-Sign went live. Yet, there are also indications that success rates were bound to decline as Election Day drew closer, and that E-Sign may have mitigated these effects in a positive way. Overall, there are more positive indicators than negative ones for E-Sign’s efficacy at increasing registration rates, turnout, and absentee voting behavior.

Background

Two of NCO’s most-used tools in the 2018 election included a registration portal and a page to help potential voters request absentee/mail-in ballots. In general, these pages helped voters fill out and print the necessary forms for voter registration or absentee signup in their state. Voters would then mail in the printed forms themselves. In certain states, however, NCO implemented a feature called E-Sign. This feature gave voters a choice: print and mail the form themselves, or make an electronic signature to the form and allow NCO to submit the form to the appropriate state or county authority on their behalf.

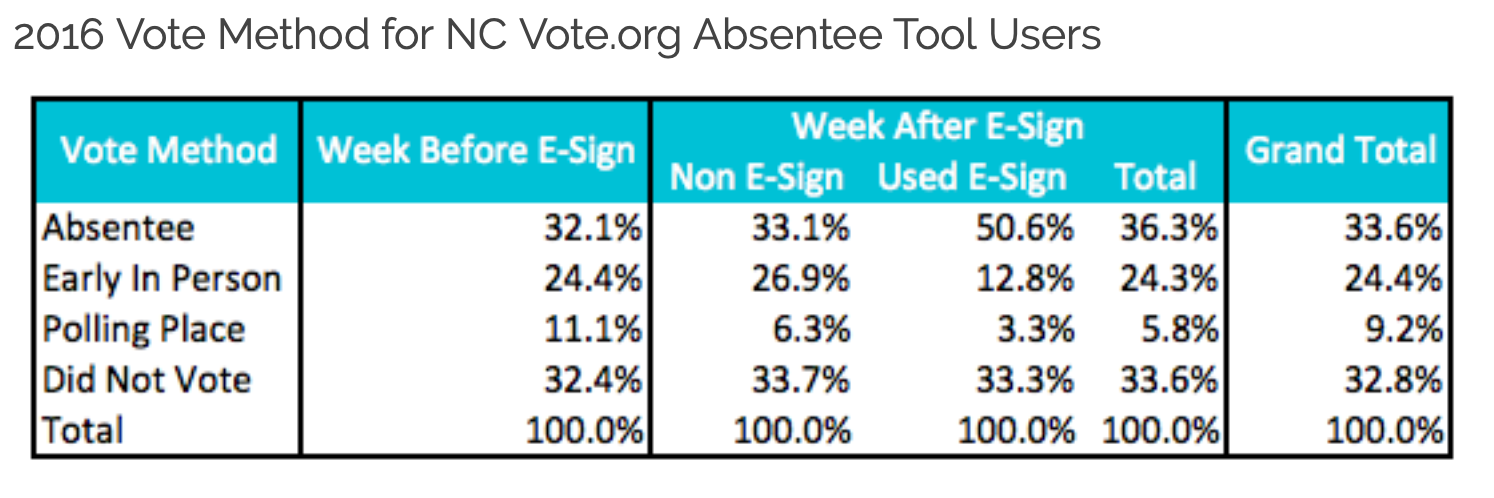

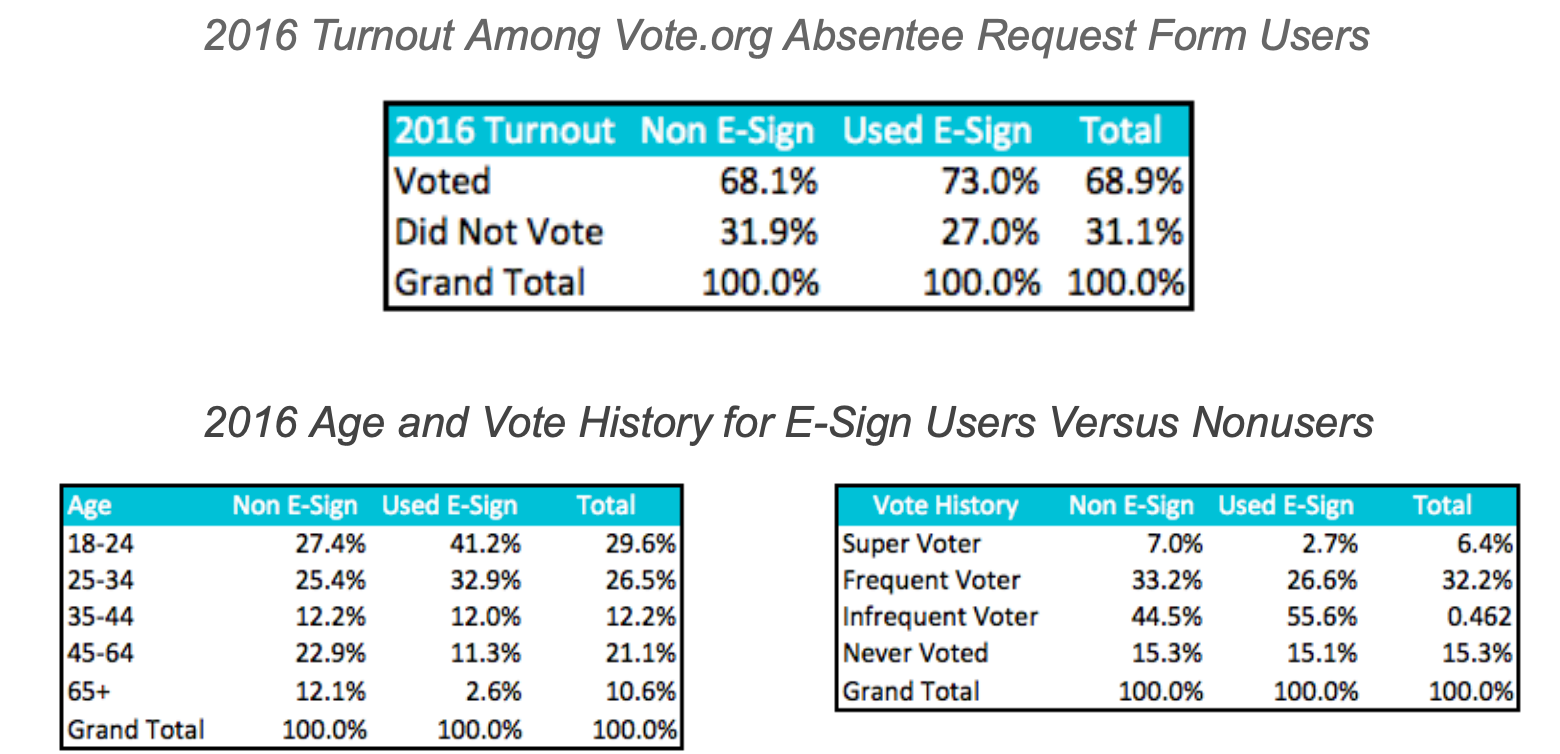

NCO had previously implemented E-Sign for absentee signup forms in 2016 in a few states. Following the 2016 election, Pantheon Analytics examined the results of the program. Pantheon evaluated the effects of E-Sign on turnout and vote method by focusing on those voters who used NCO’s absentee page just before and just after E-Sign’s debut. In at least some states, there were indications that E-Sign succeeded in getting more users to successfully convert to absentee status. In North Carolina, for instance, absentee voting was higher among people who used NCO’s tool in the week after E-Sign’s debut than among the previous week’s users – and much higher among those who actually did choose E-Sign, versus the printable PDF.

Additionally, the 2016 analysis found that overall turnout was higher among those who chose E-Sign versus those chose the printable PDF, despite the fact that E-Sign users were more likely to be young and/or infrequent voters.

Of course, the 2016 analysis was observational in nature, and in some states the turnout rates and/or absentee voting rates were not higher during the periods when E-Sign was available. The 2016 analysis was promising, but ambiguous since self-selection could have influenced the results.

The analysis in this memo is a follow up, examining the trends in turnout and registration among users of NCO’s tools before and after the E-Sign tool was implemented in the 2018 election. Likewise, the memo analyzes the differences between those who chose E-Sign and those who didn’t during the periods when both options were available.

Analysis Methods

In order to analyze the results of E-Sign on overall turnout (and on vote method, in the case of the absentee tool), this report compares users in the seven days before E-Sign debuted with users in the seven days after. This method does not give us a perfect control group: for instance, the first person chronologically included in our sample was taking action a full two weeks earlier than the last person included. The type of person who bothers to take these actions four or five weeks before an election could be different in substantive ways from the type of person who takes those same actions two or three weeks before the election.

However, comparing one week of users to another week of users helps us avoid other issues, such as potential day-of-week effects (ex. differences between weekend users vs weekday users). This method also allows us enough sample on either side of the cut point to -- potentially -- observe more than mere noise.

In addition to this before/after analysis, we perform further observational analysis of those who chose E-Sign versus those who did not. While this method is vulnerable to self-selection biases, we attempt to contextualize the results by looking at users pre-existing vote propensities. We perform both types of observational analysis for each of the E-Sign tool variants (absentee signup form and registration form).

Implementation Timeline

The timing of the E-Sign implementation varied by state. E-Sign for the absentee tool was available for users in North Carolina on October 10th, 2018, in Florida October 13th, and in Alaska, Arizona, Washington DC, Idaho, Kansas, Maryland, Oklahoma, and Vermont on October 17th. For the registration tool, E-Sign was rolled out on August 30th in four states (Alaska, Colorado, Kansas, South Carolina), and at various points in September in Texas and DC.

Voter File Match and Deduplication

Because users of the registration and absentee/mail-in tools had to enter their information into NCO’s forms, there was a robust dataset available for matching to the voter file. Match fields included first and last name, address, and date of birth, which were fed into the matching tool provided by Civis Analytics’ Platform. Overall, 87% of records in the absentee tool userbase matched, consistent with other analyses. Match rates were slightly lower for users of the registration tool, with an average of just over 80%.

Of the 54,115 matching records in the user base for the absentee tool, several thousand were duplicate records for users who had used the tool more than once during the period studied. Likewise, over 2,000 of the 13,753 records in our registration tool database were extra records for the same users. For the analyses below, we chose to exclude all but the final instance for each user. For example, if a user entered their information into the tool at 3pm and then again at 4pm, we chose the latter instance to include in the analysis. We theorize that if a user comes back to use the tool again, it is an indicator that the earlier submission may have contained errors – and so their final interaction would probably be the most meaningful “use case” for analysis purposes.

Absentee Tool Analysis

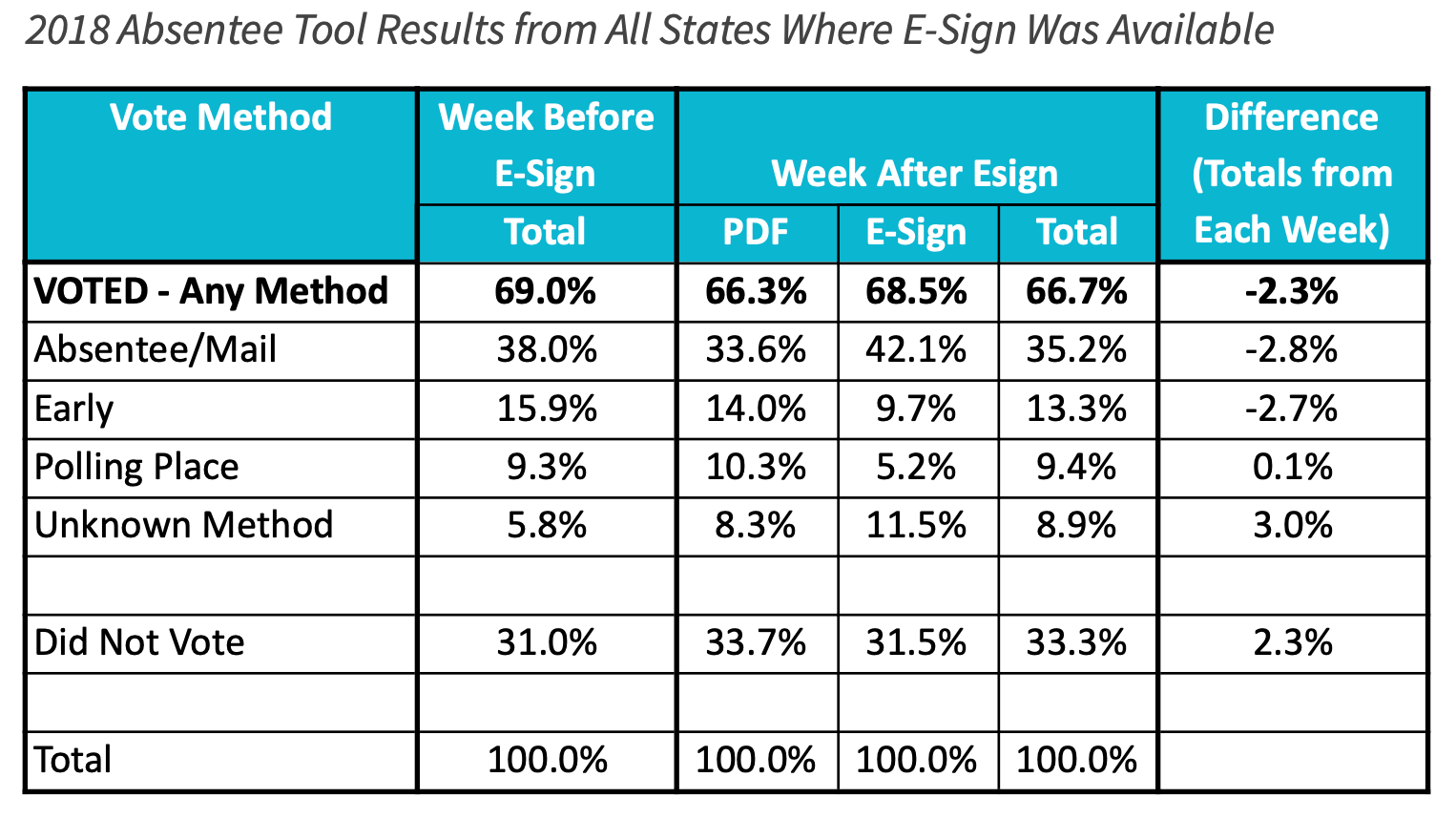

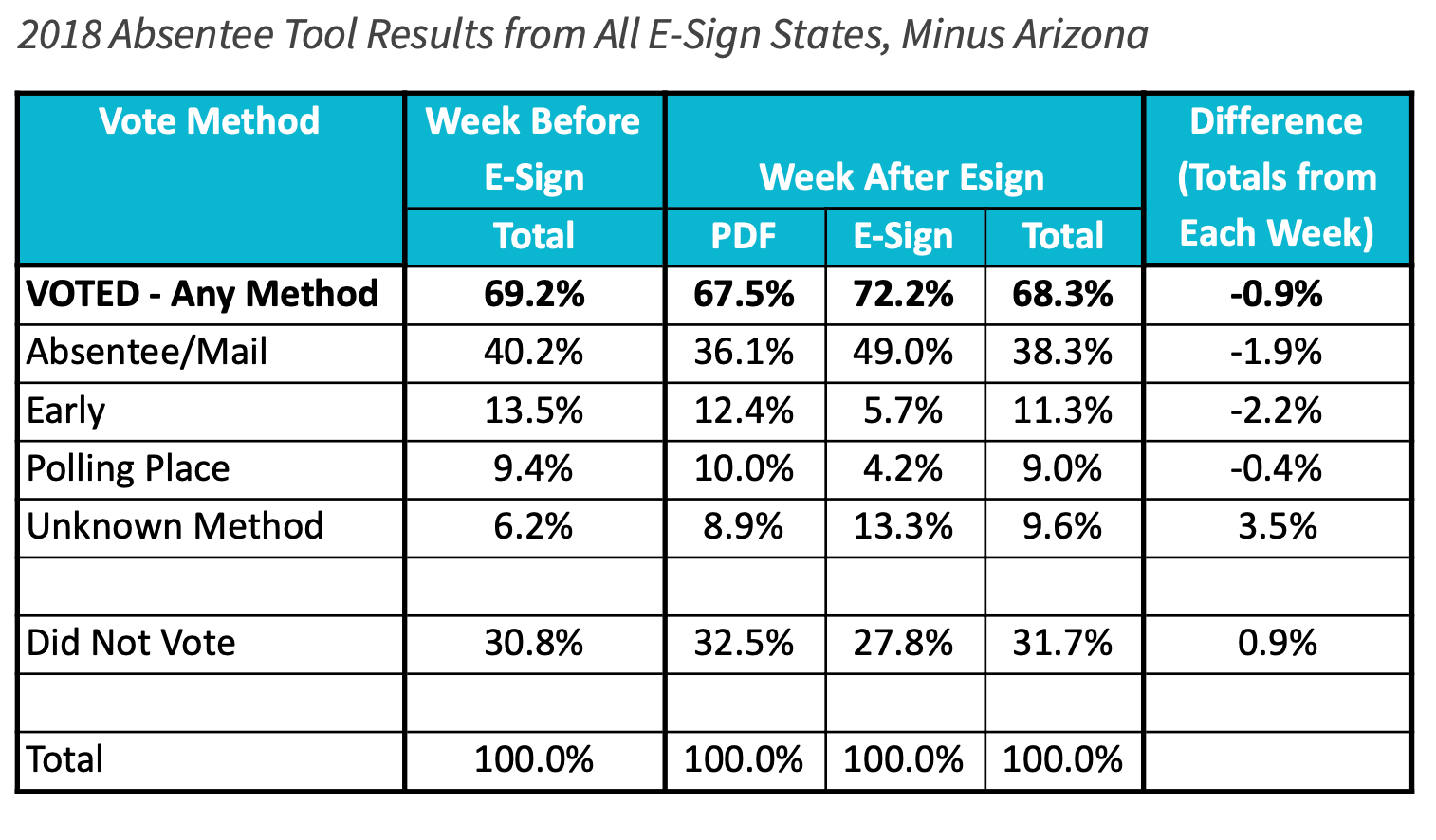

In the overall sample, users who engaged with the absentee/mail-in tool the week aer E-Sign was rolled out were slightly less likely to turn out to vote. In particular, they were less likely to vote early or absentee. The difference in the latter category is concerning, given the fact that E-Sign was designed to make it easier for people to sign up for absentee. Voting via “unknown polling method” – a voter file designation with various interpretations depending on the state – was higher among users during the week after E-Sign debuted.

Among those who did choose E-Sign during the week it was available, absentee and turnout rates were higher than among those who did not choose E-Sign. See the next section for further analysis of these differences. In this section, though, we will focus on the differences between the totals from the first week versus the totals from the second week (because it is unknown who would have chosen E-Sign had it been available in the first week).

As the Appendix explores in detail, some of the difference in turnout and vote method is driven by a particularly negative result in Arizona. Arizona is a unique case where absentee/mail voting was already very high, with nearly three quarters of the state already on the permanent absentee list. The remaining population of voters who had not already signed up for absentee status – particularly those who came to NCO trying to sign up close the application deadline – may have been substantively different from the rest of NCO’s user base. The table below shows the totals with Arizona excluded.

Without Arizona, the turnout gap is smaller at nine tenths of a percentage point. Absentee and early voting rates are lower in the post-E-Sign week than in the previous week, while “unknown method” voting is higher.

What to make of the shis in voting methods? One explanation for the “unknown method” increase may be that last-minute users of NCO’s absentee tool were more likely to vote at the last minute as well, and that states are more likely to have incomplete information on the vote methods of last-minute voters. Alternatively, the “unknown method” category may include provisional ballots. NCO may wish to investigate whether late-stage users of their absentee tool (and E-Sign users in particular) are more likely to experience challenges that require provisional balloting.

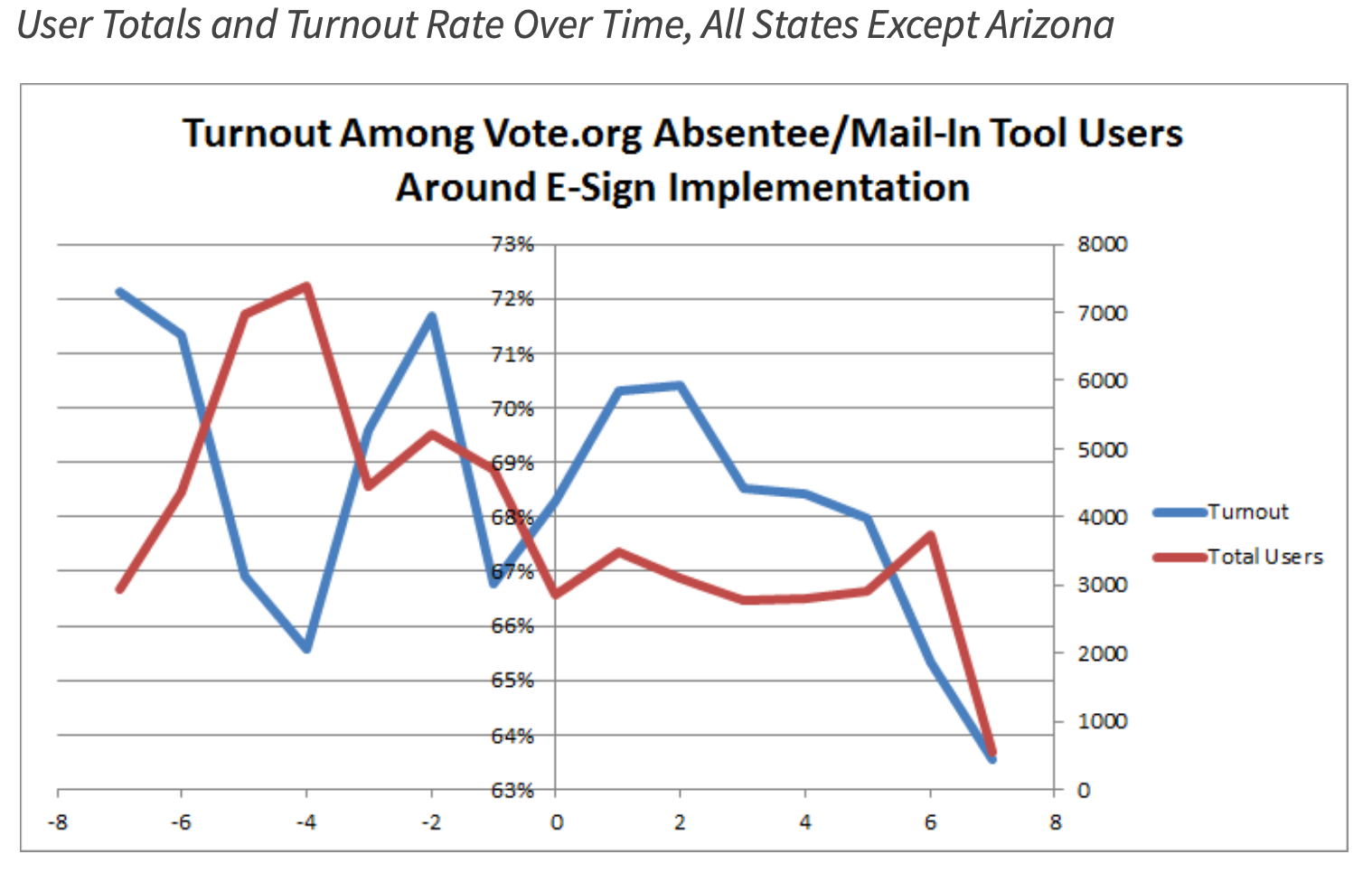

It is also important to remember that our comparison groups – two individual weeks of users – are are not randomized groups. Indeed, further analysis indicates that these populations may be different in ways that are unconnected to the intervention. One notable trend is that aer E-Sign was rolled out, the total volume of users was considerably lower. Additionally, on a day-by-day basis, turnout dropped in the final several days of the time period studied, which may indicate a more general time-related difference, rather than a negative effect of E-Sign. A downward effect over time could perhaps be expected because of logistical problems as the deadlines approached and there was less time to navigate them.

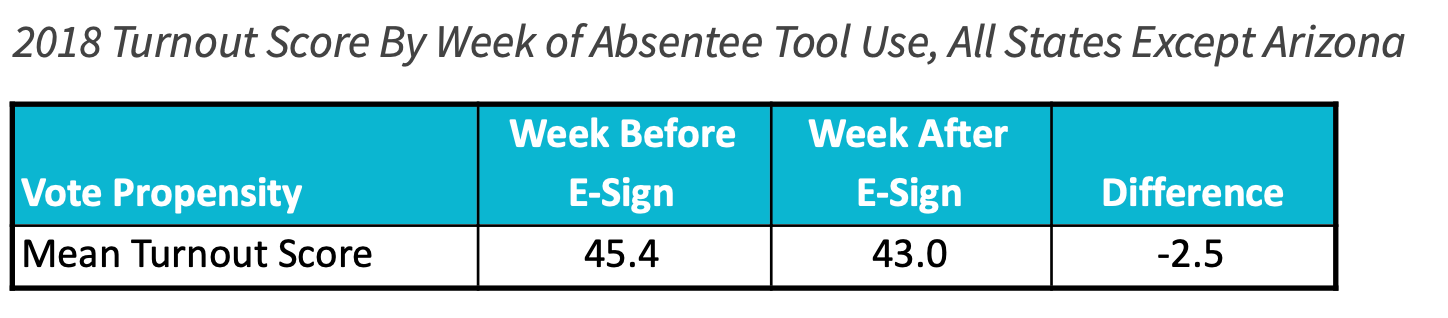

As discussed previously, there could simply be substantive differences between the type of user who took action on their absentee status closer versus farther from the absentee deadlines – even if the difference in days is not huge. Another possibility is that if NCO received organic traffic from specific incidents on specific days (for example, a celebrity tweeting out a link), the pre- and post-E-Sign audiences may have been inconsistent in ways we could not anticipate. Finally, it is worth noting that there was a small but meaningful difference in the average vote propensity score for users from the two different weeks.

Since this difference in expected turnout is larger than the actual turnout difference, it reduces the concern that debuting the E-Sign tool may have negatively impacted turnout.

E-Sign vs. PDF Users of the Absentee Tool

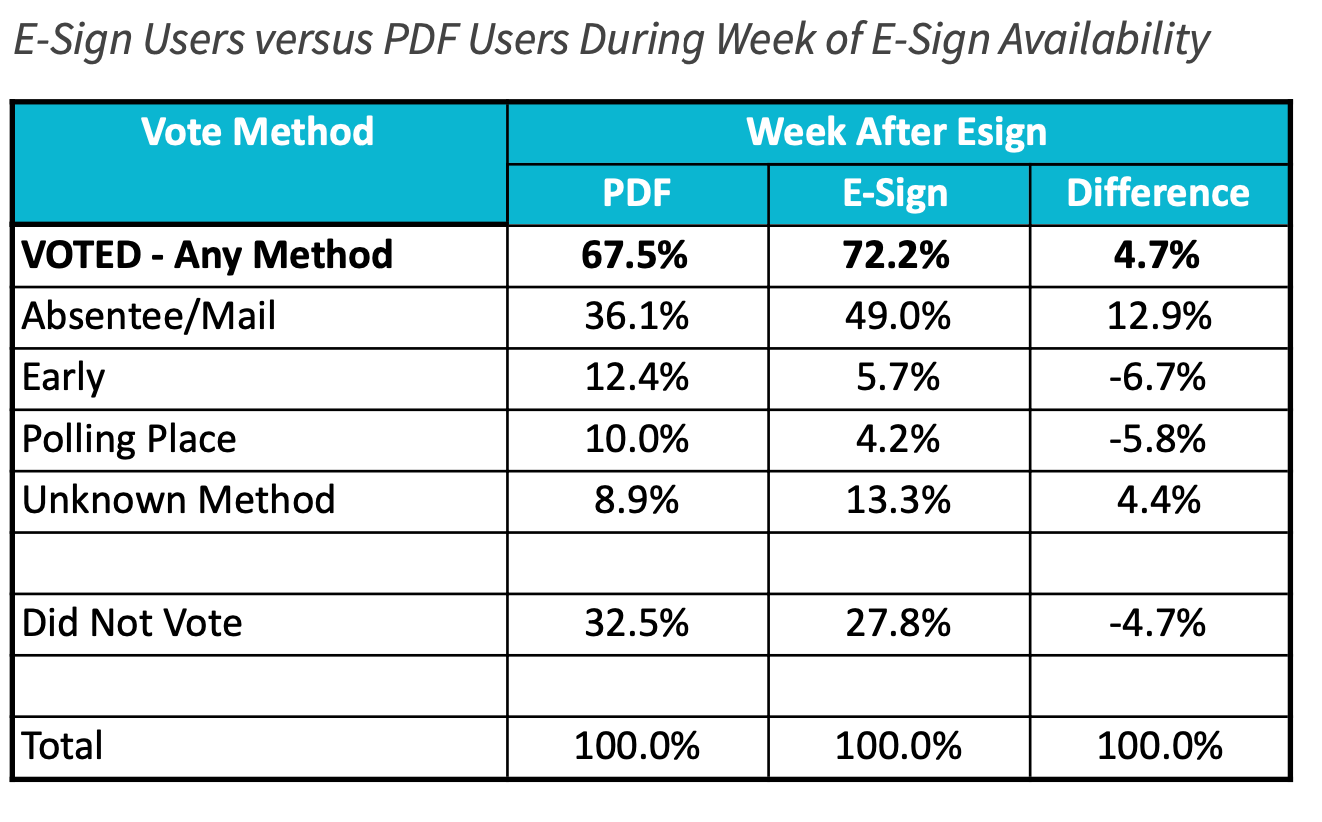

In the period after E-Sign debuted, users had a choice of which method to use (E-Sign or printable PDF). Comparing the groups who chose one versus the other cannot account for unknown self-selection factors. Still, it is worth observing these differences for the sake of getting indications – if not outright evidence – of the effects of E-Sign. (All analyses in this section exclude Arizona.)

A key finding is that E-Sign users were much more likely to vote absentee than those who chose the print-your-own PDF option. Since all users ostensibly visited this particular NCO page in order to sign up for absentee status, the 13-point improvement in successful absentee voting can be considered a rousing success. In exchange, E-Signers had lower rates of early voting and Election Day voting at polling places – though higher rates of “unknown method” voting.

In terms of overall turnout, the E-Sign users bested the PDF printers by 4.7 points. It is tempting to chalk this up merely to self-selection. Perhaps the type of person who chose E-Sign was a more eager voter anyway. For instance, if people who chose E-Sign had a higher vote propensity scores than people who chose to print the PDF, the 4.7 point difference in turnout would be understandable. However, in examining the pre-existing vote propensities of each pool, we find the opposite.

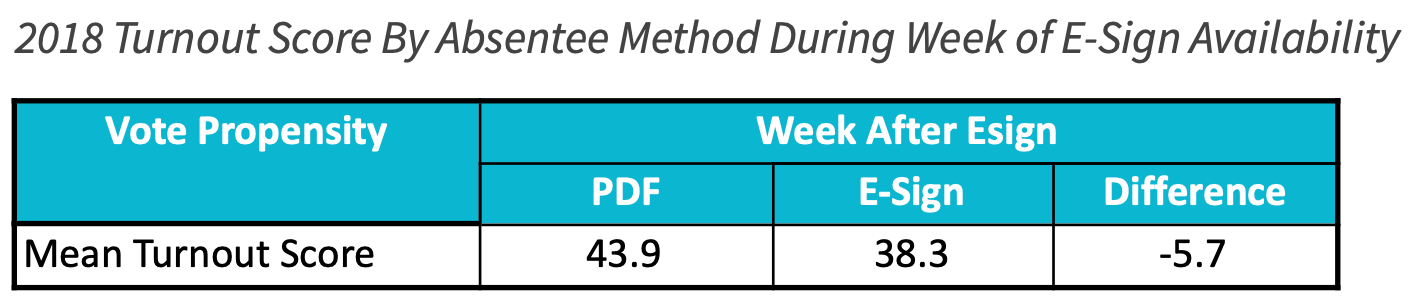

The 2018 vote propensity scores for E-Signers was 5.7 points lower than among the PDF printers. This follows the same pattern seen in 2016: people who chose E-Sign were less frequent voters, and yet they ultimately voted at higher rates than those who didn’t choose E-Sign.

Could E-Sign have made the difference? Quite possibly -- although it is worth noting that both groups outperformed their predicted turnout by significant margins. Even among the PDF printers, for instance, the turnout rate of 67.5% far outpaced the average turnout score of 43.9. We have seen from other research that NCO users are uniquely self-motivated in ways that their turnout scores cannot have anticipated. Perhaps the self-motivation of people who chose E-Sign was especially strong, which could account for their extra over-performance. This alternative explanation is, though, a more complicated one. The simpler and likelier explanation is that E-Sign did, indeed, contribute to higher turnout.

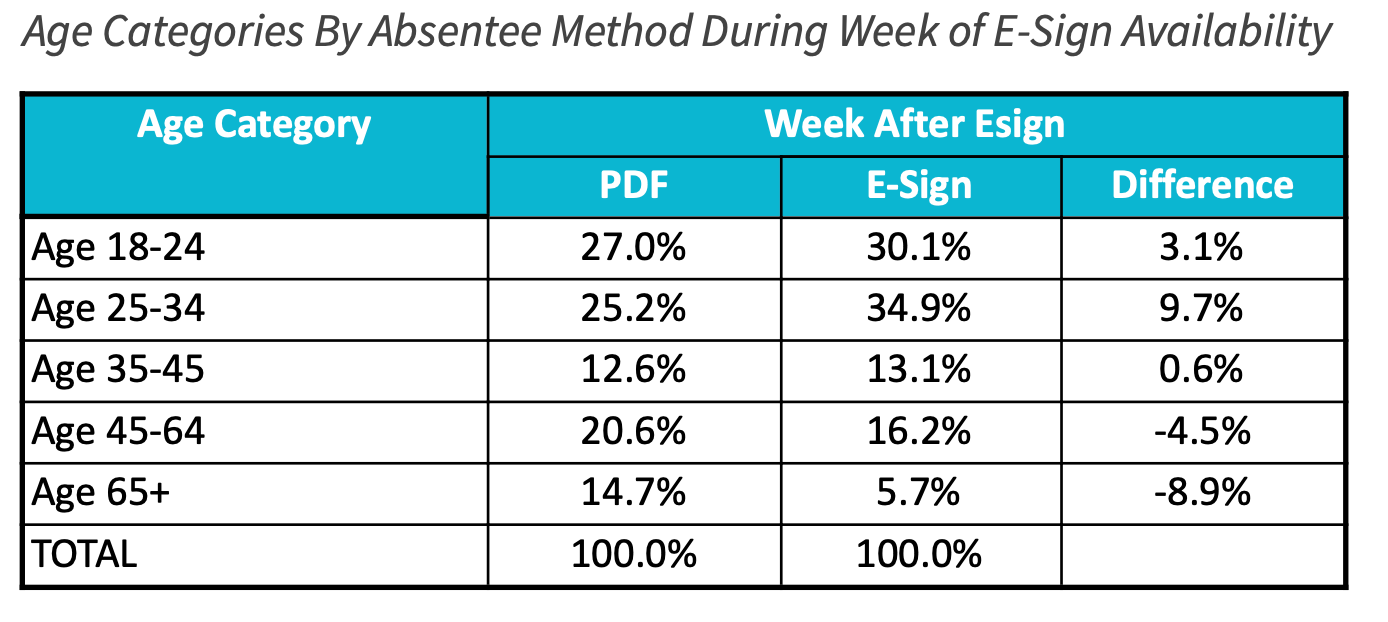

Unsurprisingly, we can see that the E-Signers tended to be younger than those who chose to print. (Age is a major factor in turnout models, so this is doubly unsurprising, given the above finding about turnout scores.)

Younger users may be less likely to have access to a printer. They may also feel more comfortable with electronic transmission methods (and less interested in mailing a stamped letter).

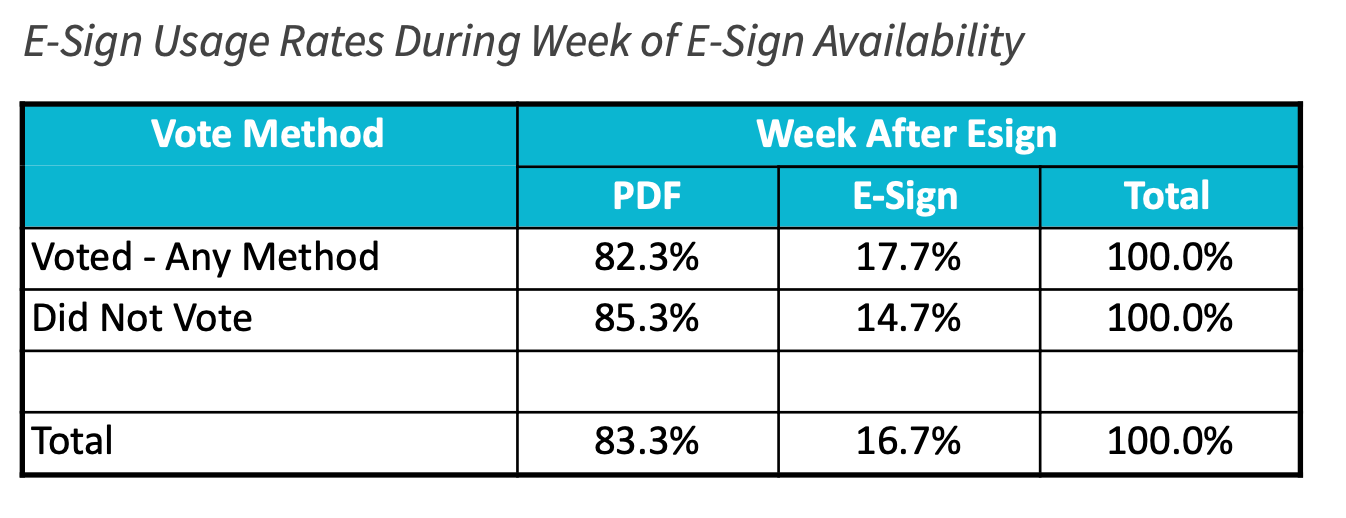

Finally, it is worth noting that users who chose E-Sign were a minority of all users. Around 17% of users chose E-Sign. If E-Sign does indeed have a positive effect on turnout (and self-selection is not the driver of the above findings), then NCO may wish to add more encouragement or “nudge” language to its absentee tool to induce more users to choose E-Sign.

Registration Tool Analysis

In a few states in 2018, NCO debuted its E-Sign tool for the purpose of voter registration, not just absentee signup. On August 30th, Alaska, Colorado, Kansas, and South Carolina, users were given the option to either E-Sign their registration form, or to print a paper form, or to be redirected to their state’s online voter registration system. District of Columbia users were given the same options on September 18th. Finally, in Texas, users from certain counties had E-Sign as option for a patchwork of time periods, owing both to technical issues and to pushback from local officials.

To measure the success of NCO’s registration tool, we examine the rates at which voters in the particular subgroups matched to the voter file. Someone who did not successfully register would not be able to match. It is, of course, possible that someone could fail to match for other reasons (differences in data entry, for example). But the Civis matching tool is fairly reliable; most non-matchers should be understood as unsuccessful registrants.

Multi-State Registration Tool Analysis

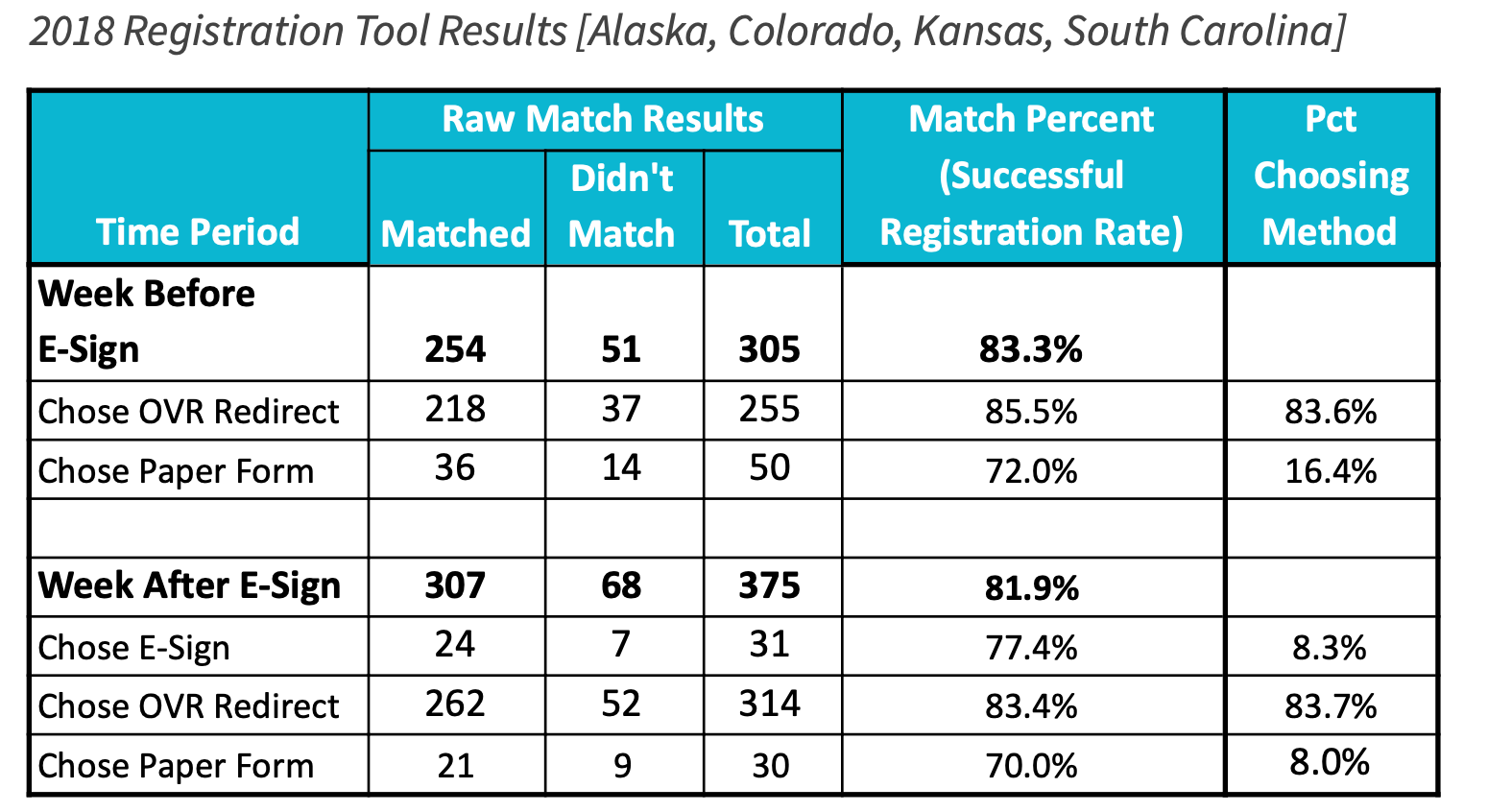

While the raw numbers in these states are relatively small, some patterns emerge. In the jurisdictions aside from Texas, the overall rate of successful registrations was similar in the week before and the week aer E-Sign debuted (83.3% versus 81.9%). Before E-Sign’s debut, there was a marked difference in the success rate of those who chose to print paper forms versus the majority who chose the online voter registration option (in which users were redirected to the state’s online registration page).

The OVR option was more successful by over 13 points. In the week following E-Sign’s debut, Among those who chose E-Sign, the registration rate was approximately halfway between the success rate of the paper form and the success rate of the OVR redirect.

In the future, NCO may wish to eliminate the option of allowing either E-Sign or print-your-own registration form, and instead direct all users to the state’s OVR page. The success rates were higher for OVR in both weeks. However, if NCO does keep the print-your-own option, then E-Sign appears to be a good third option to include. Based on the percentages of users who chose each method, it appears that the E-Sign option draws more people away from the print-your-own method than from the OVR method.

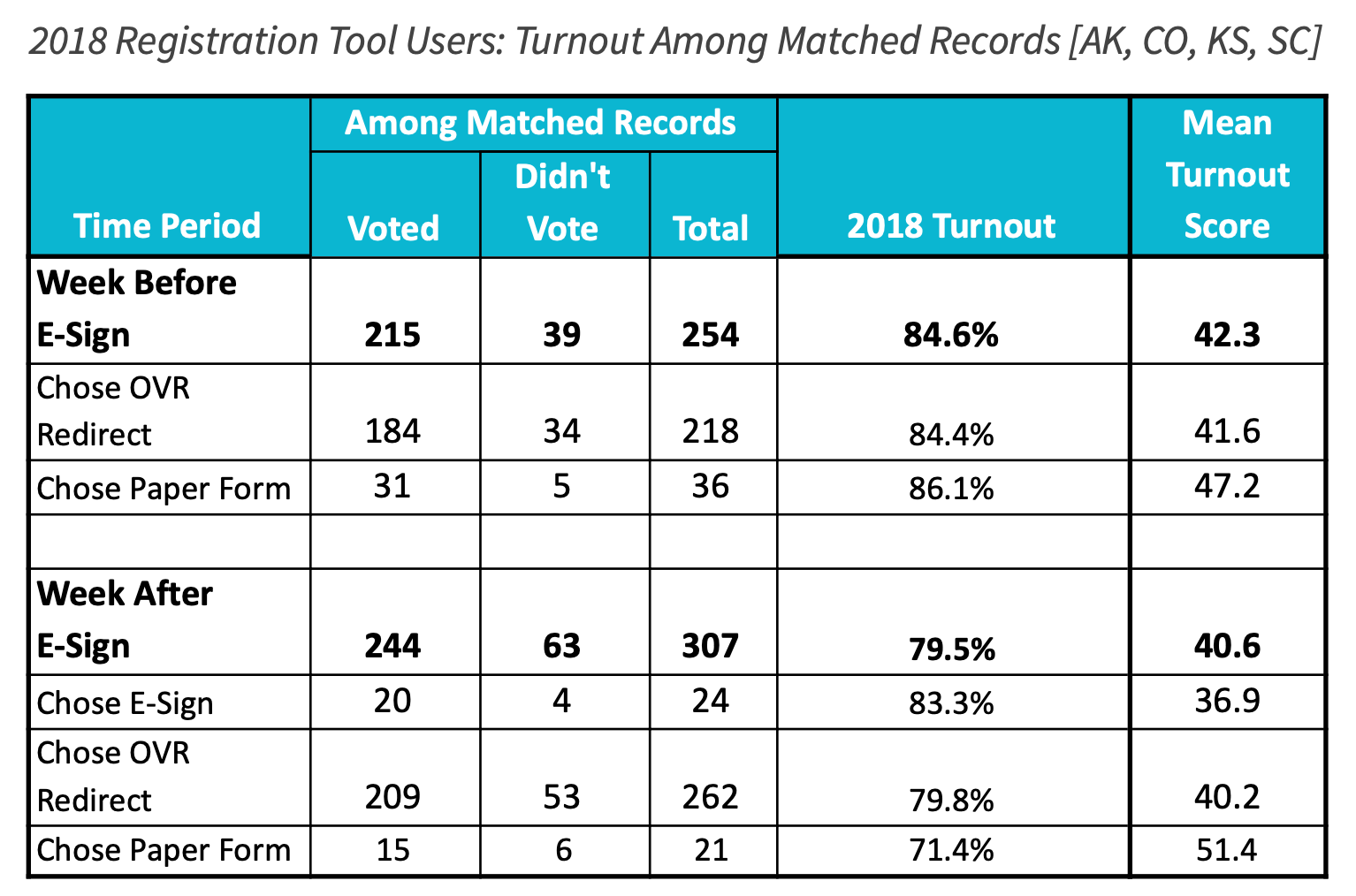

For the registration tool users who did match to the voter file, a similar turnout pattern emerged as with the absentee tool:

E-Sign users were more somewhat likely to vote than those who had chosen other methods. Yet again, this higher actual turnout contrasted with lower average turnout scores among E-Signers. It is still difficult to establish whether this discrepancy is due to the positive effects of E-Sign, or whether self-selection is correlated with factors that made the turnout model uniquely erroneous for this particular subgroup. It is also worth noting here that the sample sizes are very small.

Texas Counties Registration Tool Analysis

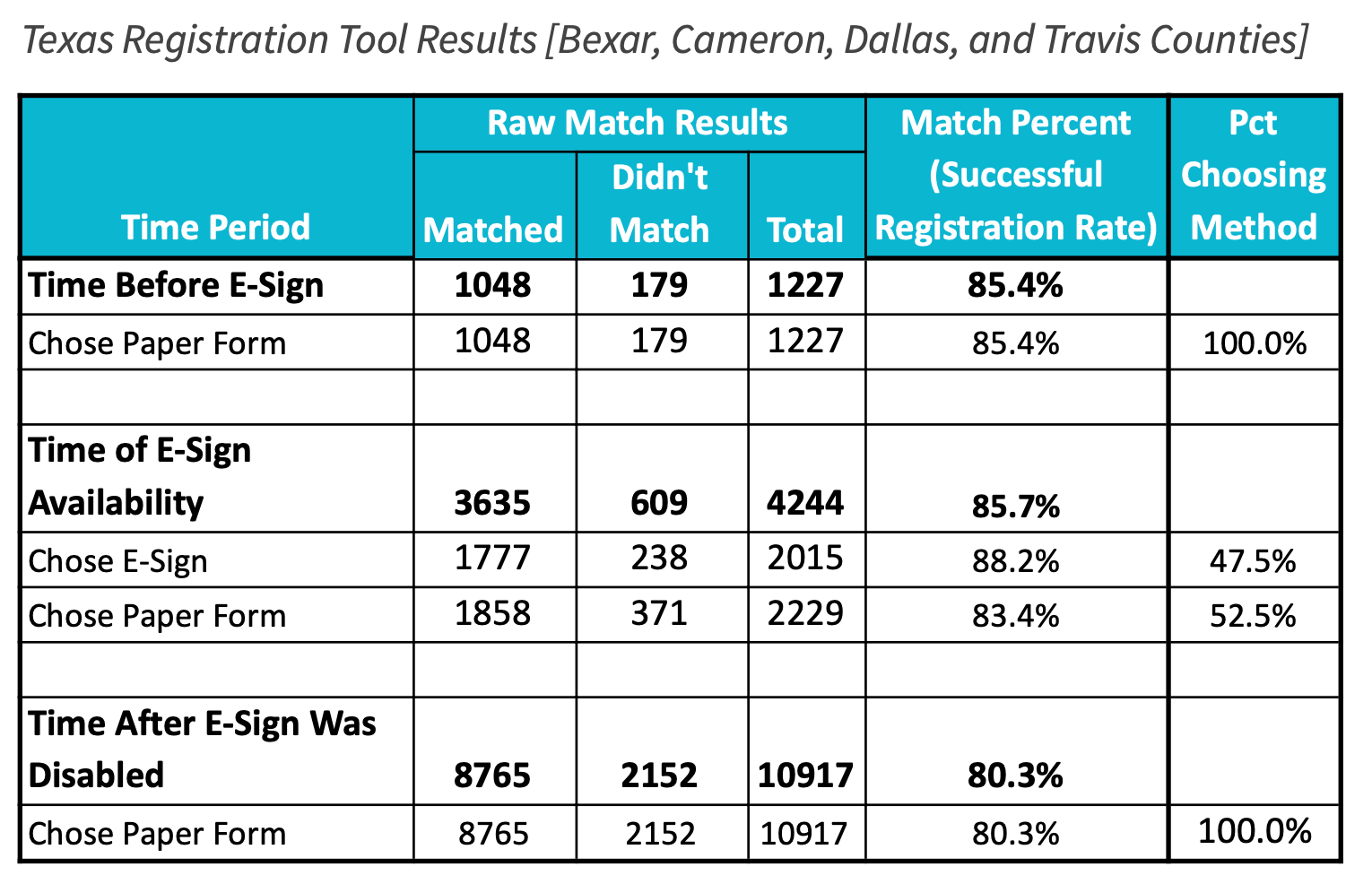

In Texas, E-Sign was rolled out in four counties (Bexar, Cameron, Dallas, and Travis) on September 20th and 21st at varying times. Cameron County’s E-Sign feature was disabled on September 28th because county officials said that they would be asking E-Signers to fill out a paper form anyway, essentially having them register twice. E-Sign in the other three counties was disabled on October 2nd.

The analysis below shows the registration (match) rates for Texas users in the time periods before, during, and aer E-Sign was available in the particular counties. The first two time periods are slightly longer than one week, while the latter period is slightly shorter (except in Cameron county) due to data limitations. Texas does not allow online voter registration, so this option was not present during any time period.

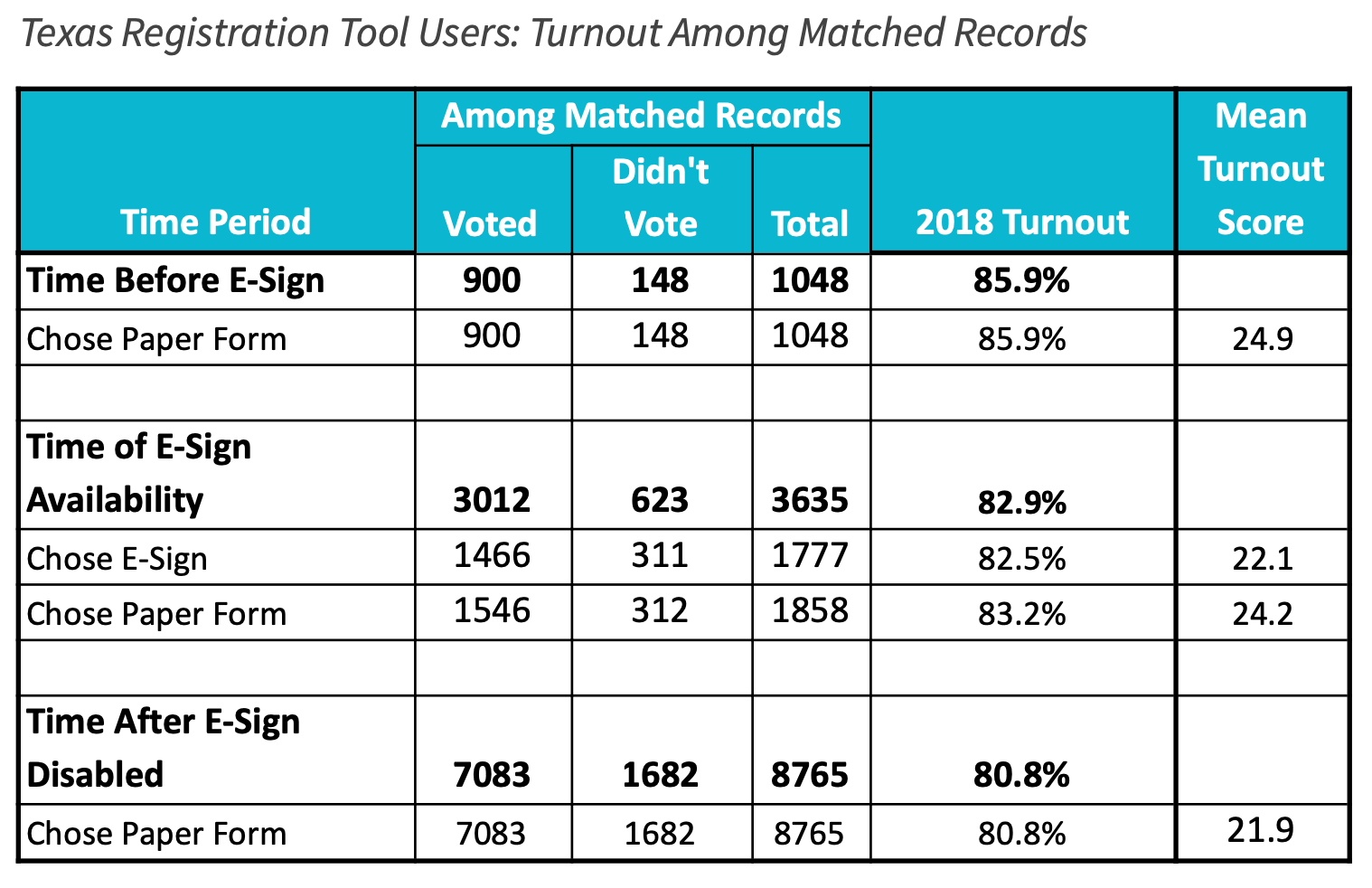

In Texas, E-Sign was a much more popular option than in the other states, with nearly half of the registration tool’s users choosing E-Sign during the period it was available. E-Sign once again saw a somewhat higher rate of successful matching to the voter file than seen among the PDF printers.

Among those who matched, E-Signers had slightly higher turnout than those who chose the printable form, again despite having lower average turnout scores. But the differences were much less pronounced than among other analyses. The very low turnout scores (but very high turnout numbers) once again demonstrate that NCO users are self-motivated in ways that their turnout scores are incapable of accounting for.

It is also notable that, once again, success rates declined during the time period closest to the election. In this case, the later time frame was one in which E-Sign was not available. If there are negative linear effects on success rates as time marches toward Election Day, then E-Sign appears to have stemmed those effects.

Conclusions

As in 2016, there were some signs in 2018 that the E-Sign tool had a positive effect on turnout and vote method. E-Signers using the absentee tool were much more likely to successfully vote absentee (and to vote overall) than those who chose to print their forms, despite the fact that E-Signers had lower vote propensity scores to begin with. Users of the registration tool’s E-Sign option also appeared to have greater success in registering than those who printed their forms (though less success than those who opted to be redirected to their state’s online registration system).

Still, observational analysis can only indicate possible effects. There is some chance that, despite their lower turnout scores, E-Sign appeals to users who are already uniquely self-motivated. It is also possible that both explanations are at play: E-Sign may be better at capitalizing upon these users’ motivation, moving them more seamlessly toward their next step in civic participation.

Appendix 1: Arizona Analysis

One concerning outcome was in Arizona. The rates of overall turnout was lower among users aer E-Sign was made available. And in particular towards the end of the period of analysis turnout shied towards polling place voting, instead of absentee/mail-in. That was especially true among users who opted to print a PDF.

Arizona is a state with very high vote by mail adoption. This may mean that the voters who have not yet signed up to become permanent mail-in voters are quite unusual, and that might be especially true as a deadline approaches. By the end of the analysis period it was October 25th, just two weeks before Election Day 2018. If there was not sufficient time for them to mail in a ballot request form, receive a ballot, and return it before Election Day, it’s possible those voters simply opted to vote in person. It’s possible that lags in that process might also explain why E-Sign users ultimately voted at a lower rate than users who opted for a PDF.

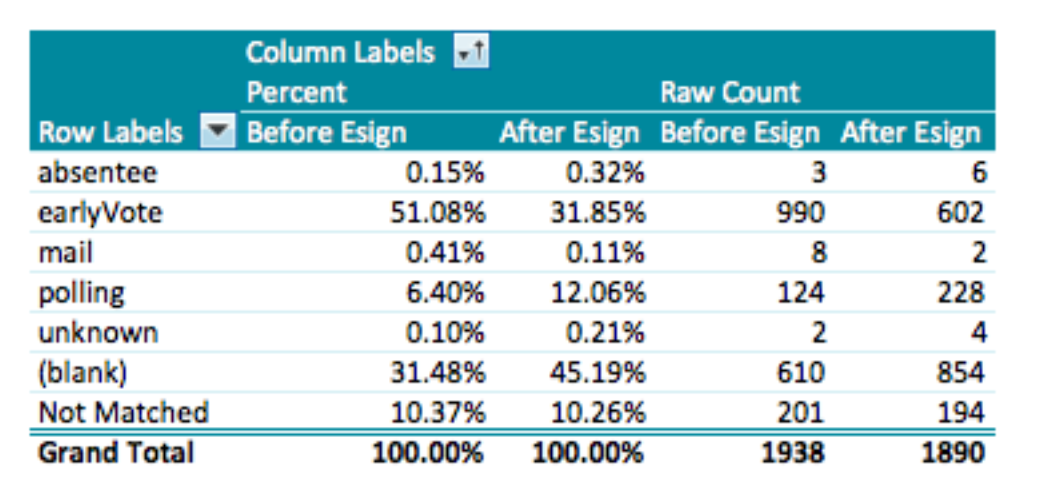

In the figures below, “(blank)” is used for people who did not vote. Additionally, Arizona’s voter file is known for its curious designation of “early vote” to mean both true early voting as well as absentee voting.

Figure 1: Vote Method Among Absentee/Mail-In Before and Aer E-Sign Availability, Arizona

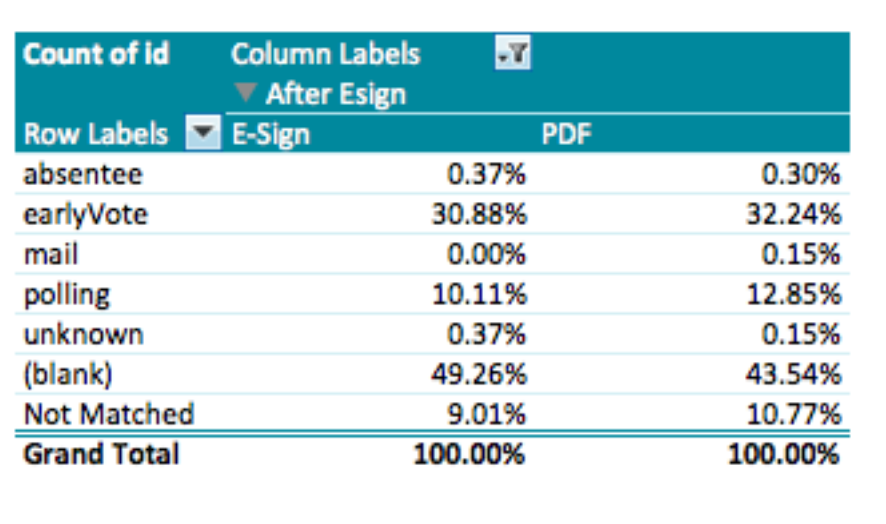

Figure 2: Vote Method Among Absentee/Mail-In By E-Sign Usage, Arizona

In the week following E-Sign’s adoption, users of both E-Sign and the PDF option were much less likely to vote than those from the week before. This suggests that it was something about the underlying population (or the circumstances that close to the election), rather than the tool itself that caused the bulk of this effect.