VoteAmerica’s November 2020 ballot chase program

Research and Analysis by Rachael Firestone, Jennifer Lauv, and Christopher Mann Memo and Additional Analysis by Scott Minkoff

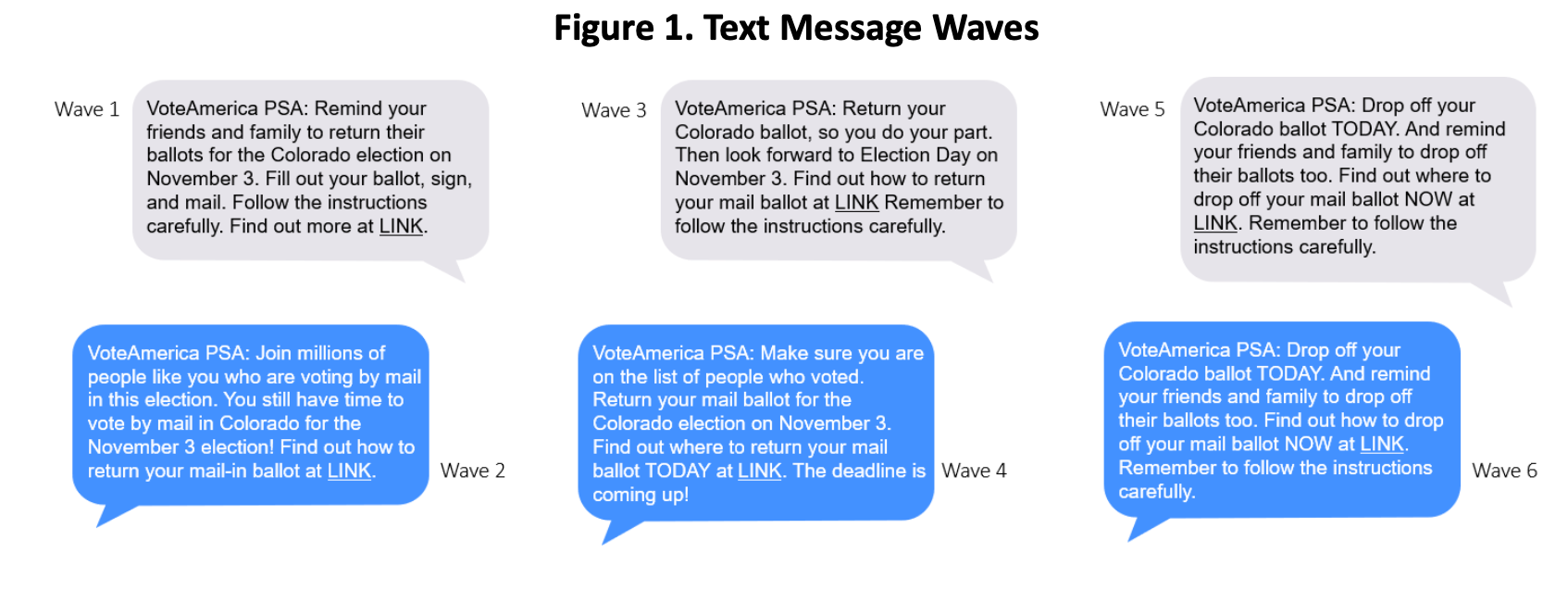

For the 2020 general election cycle, VoteAmerica ran a 17-state ballot chase text messaging (Peer-to-Peer SMS) campaign aimed at getting voters who automatically received or requested mail ballots to submit them. In total, VoteAmerica contacted 2,479,047 people. These people received up to 6 different messages. Those text-messages are presented in Figure 1. All of these potential voters were in VoteAmerica’s target universe of historically low-turnout populations including people of color, people under 35, and unmarried women.

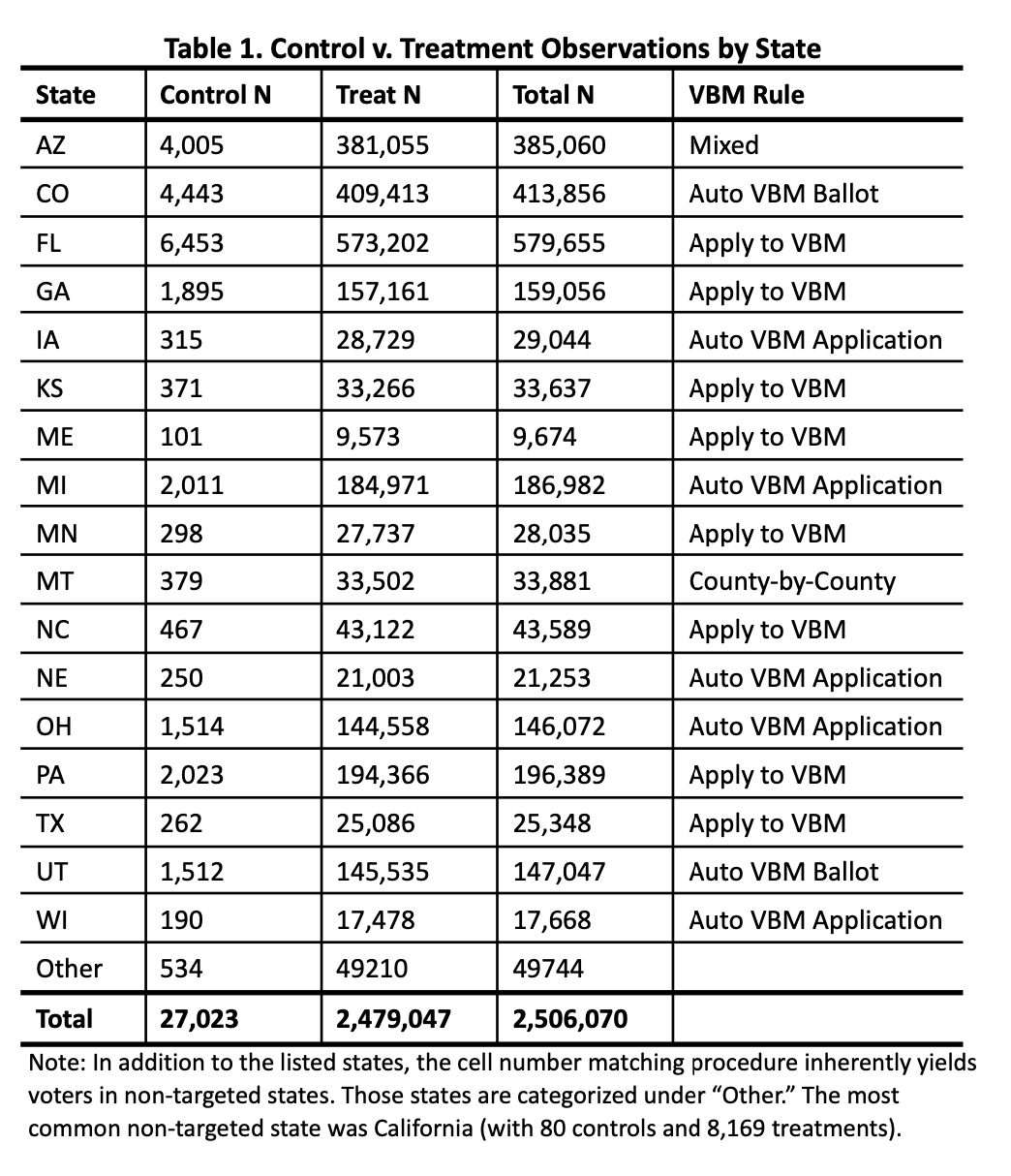

In an effort to evaluate the effectiveness of the campaign, VoteAmerica ran an experiment where a limited number of recipients were randomly selected to create a control group that would not receive ballot chase text messages. Note that in an effort to ensure that VoteAmerica reached as much of its target universe as possible, the experiment used a very small control group that included 27,023 people (1.08%) of the 2,506,070 people that were targeted. (See Table 1 for state-by-state numbers.) The goal was to compare this group to those who did receive the text messages and see if the message recipients were more likely to return their ballots.

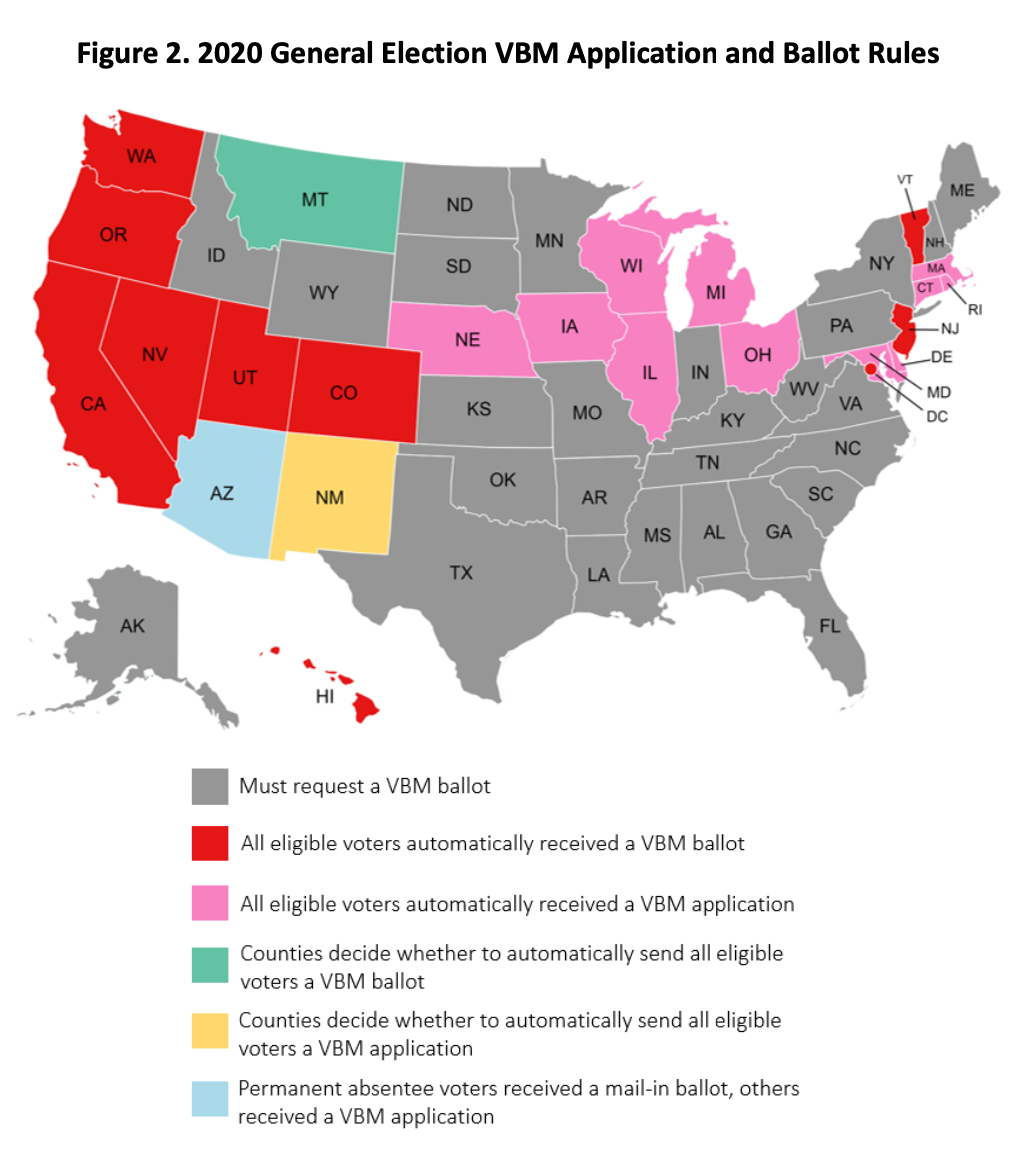

States were divided into three groups based on their vote-by-mail (VBM) ballot application rules.

- Group 1. States where voters had to request a VBM application.

- Group 2. States where all eligible voters automatically received a VBM application in the mail.

- Group 3. States where all eligible voters automatically received a VBM ballot in the mail.

These state-by-state rules are visualized in Figure 2. Note that there were three states that did not comfortably fit into these categories. In Montana, counties decided whether to send all eligible voters a VBM ballot. In New Mexico, counties decided whether to send a VBM application. And in Arizona, permanent absentee voters received a VBM ballot while others received a VBM application.

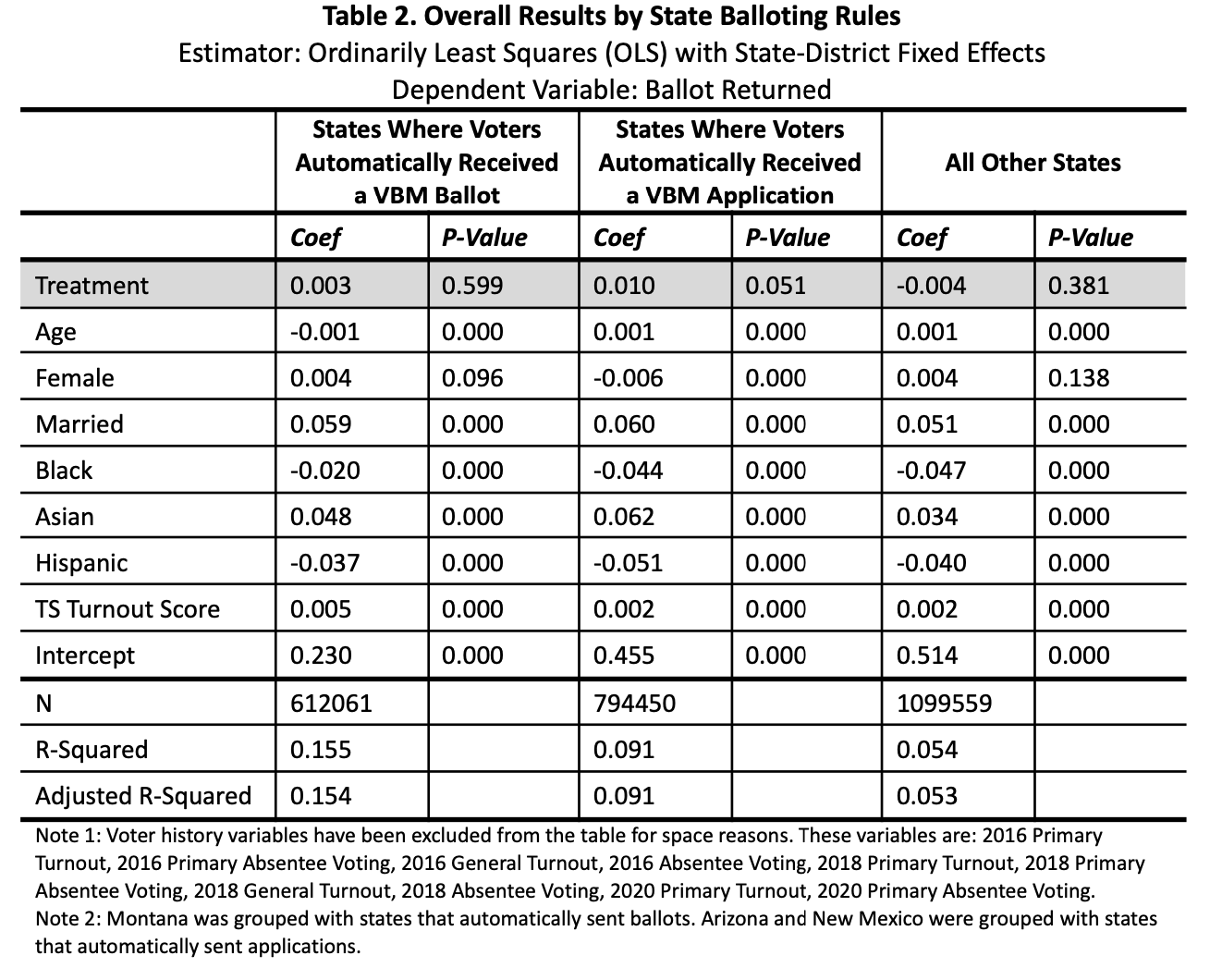

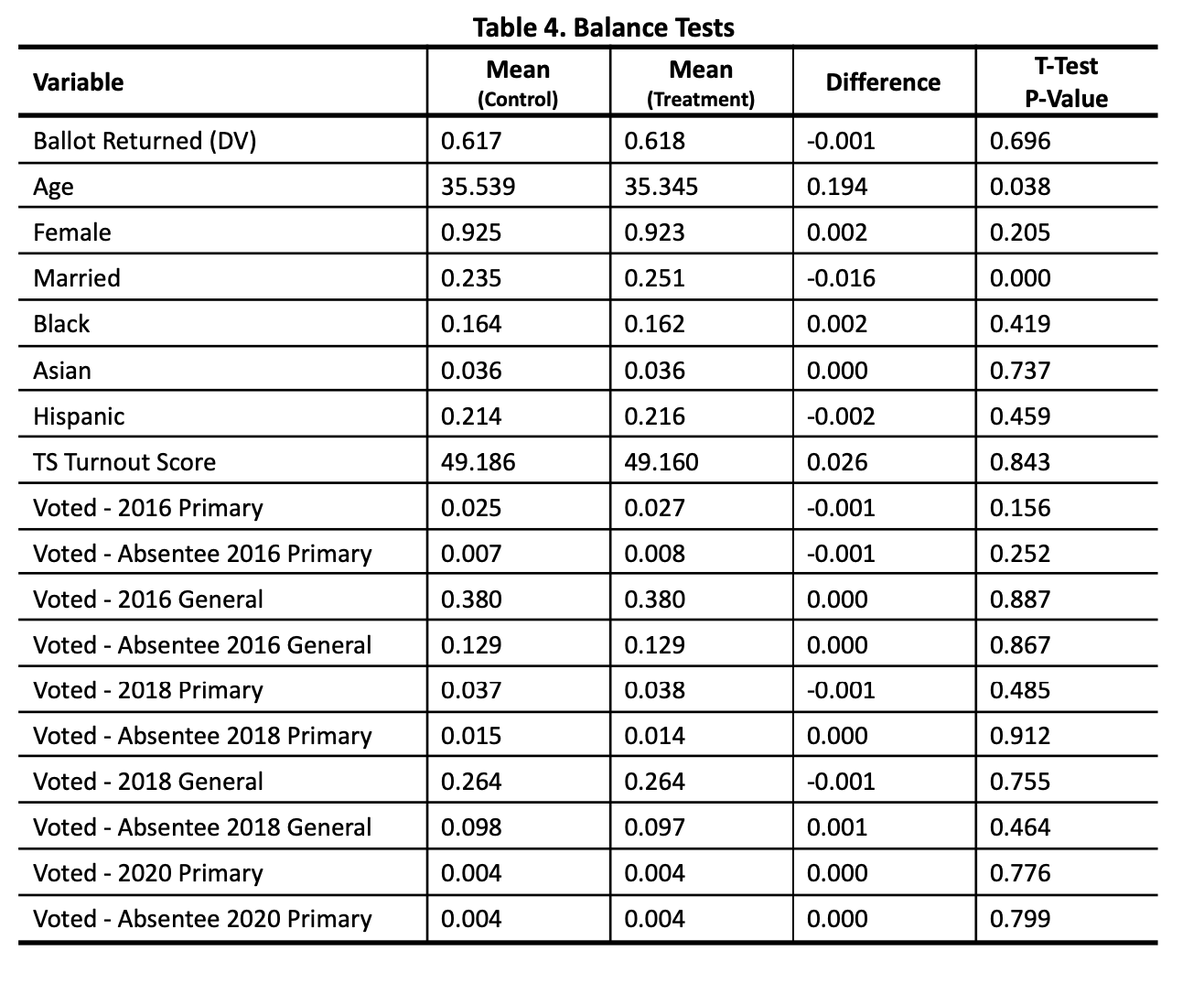

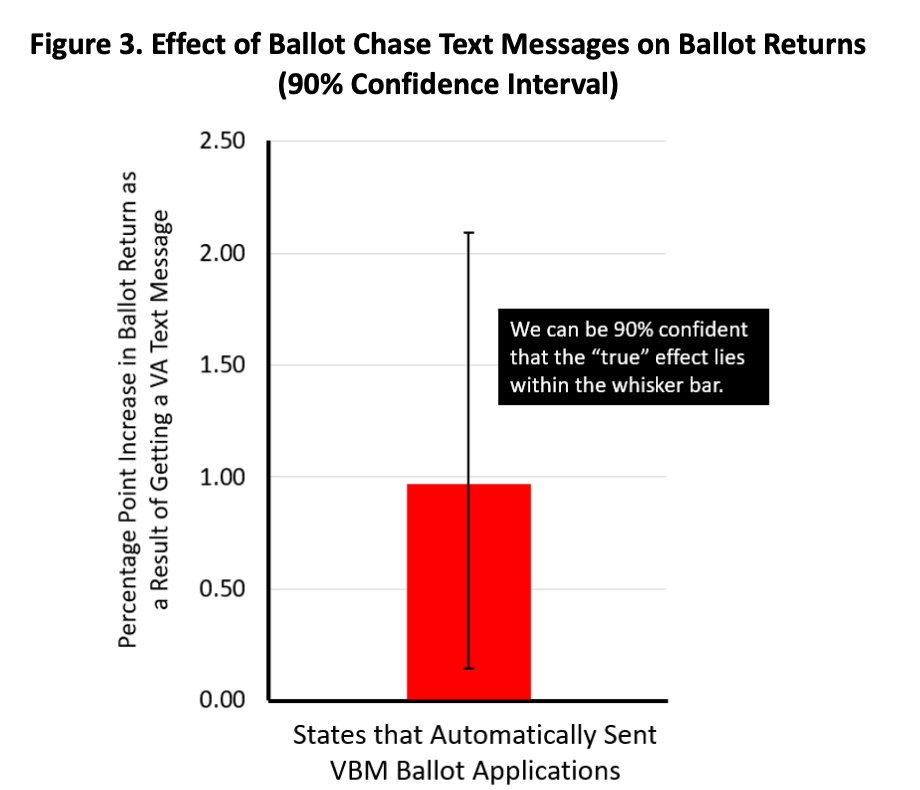

To test the effect of treatment, ordinary least squares (OLS) with state-congressional district fixed effects was used. (Logit models produce substantively similar results.) The models include an array of control variables: age, sex, marital status, race, TargetSmart Turnout Score, and voter history (turnout and use of absentee balloting). Complete results are presented in Table 2 with the treatment effect visualized in Figure 3.

The treatment effect indicates that the program was effective in states where voters were automatically sent VBM applications. The effect for these states is visualized in Figure 3 where you can see that recipients of VoteAmerica’s ballot chase text messages were just shy of 1 percentage point (0.97) more likely to submit their ballot than those in the control group. The whisker shows a 90% confidence interval (which means we can be 90% confident that the “true” effect lies within the whisker bar).2 There was a small positive (0.3 percentage points) and insignificant effect for those in states where ballots were automatically mailed to eligible voters. In states where voters must request a VBM ballot there was a negative and insignificant effect.

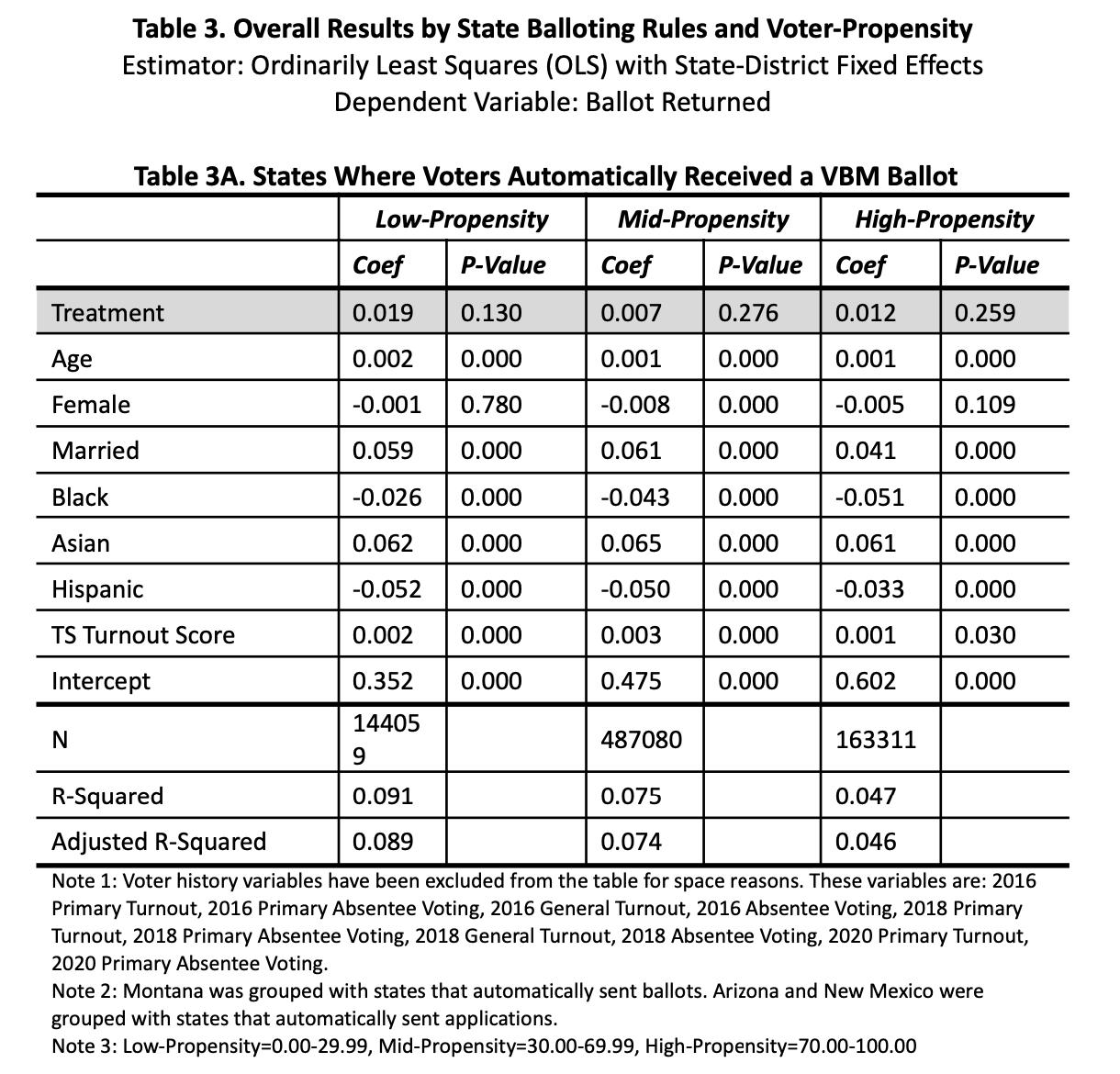

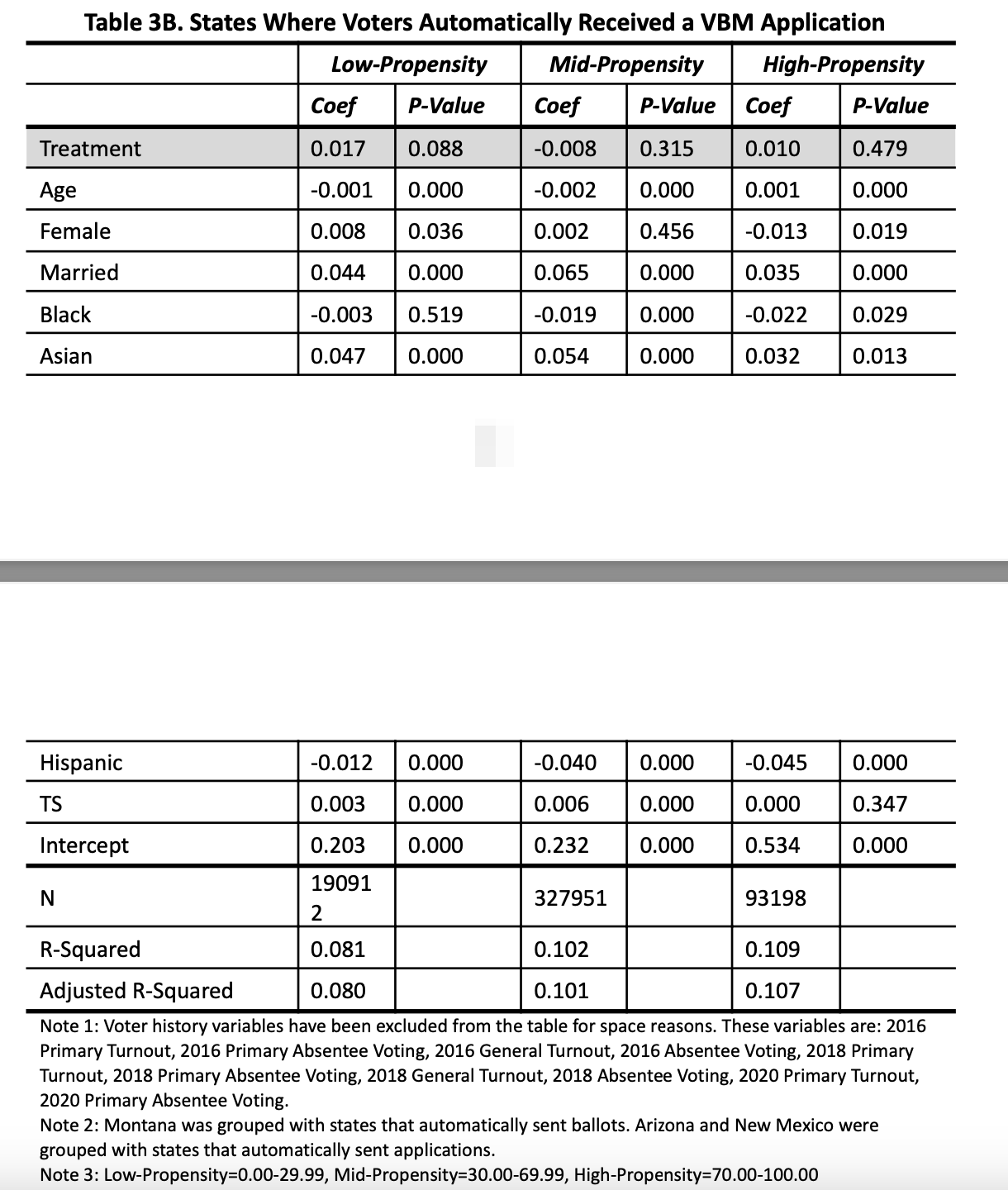

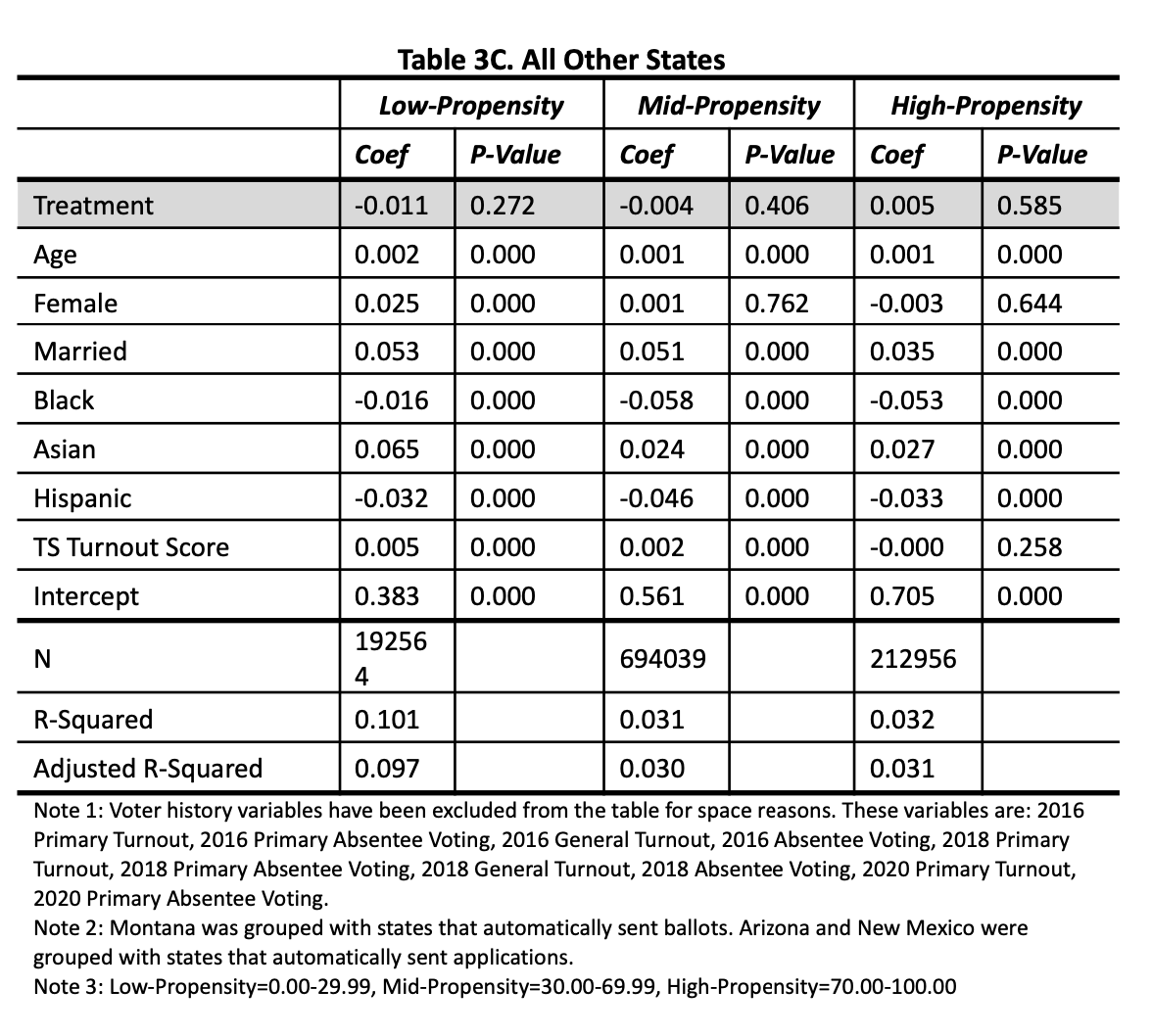

An additional analysis – presented in Tables 3A, 3B, and 3C – breaks people down based on their TargetSmart Turnout Score (low-, mid-, and high-voting propensity). Somewhat unusually, we don’t observe effects being strongest among mid-propensity voters. Instead, there is some evidence that effect is most pronounced among low-propensity voters in states that sent VBM ballot applications. There is also some (lower-confidence, p=0.13) evidence that low-propensity voters in states that sent VBM ballots responded to the text-message treatment. These propensity results may be explained by the “effect attenuation” story that has been observed in other 2020 mobilization experiments: the intense election environment – including a mid-propensity voters being flooded with GOTV contacts – reduced the actual effect of the messaging and VoteAmerica’s ability to accurately observe that effect. There continues to be no evidence that people in states where voters need to actively apply for a VBM ballot were impacted by the treatment.

This is an encouraging (if still sub-optimal) result for VoteAmerica given the electoral context of the 2020 election. The text messages appear to be most helpful in states with middle-ground VBM rules: states where VBM is not very easy (everyone gets a ballot) nor very difficult (voters have to actively apply). The state has helped voters with the first step by sending them a ballot application that they have completed, VoteAmerica is helping them with the next step of getting the ballot submitted. While a significant positive result for states that automatically sent ballots would have aligned with theoretical expectations, the positive yet uncertain result is consistent with other 2020 results. It is also worth noting that only two targeted states had automatic VBM balloting: Colorado and Utah. And in states where voters had to actively apply for VBM ballots, the absence of an effect is more expected as these voters were likely to return their ballot from the outset and the additional messaging was of limited added value.

Overall, these results are an indicator that ballot chase text message reminders can work but that the VBM application rules and the election environment likely play important roles in determining effectiveness. Depending on the electoral context, future ballot chase resources might be more efficiently used if they emphasize states where applications or ballots are sent to all voters.